Category Archives: Uncategorized

Shenanagins again and again

I’ve written a lot about “winning” hashtags and how this is a boastful tool for organizations. Here’s what I wrote yesterday on it.

I’ve also written about trickery using Twitter. Here’s a good one.

But now I have a new story…

As I was going through the Azerbaijani election hashtags, I noticed something funny.

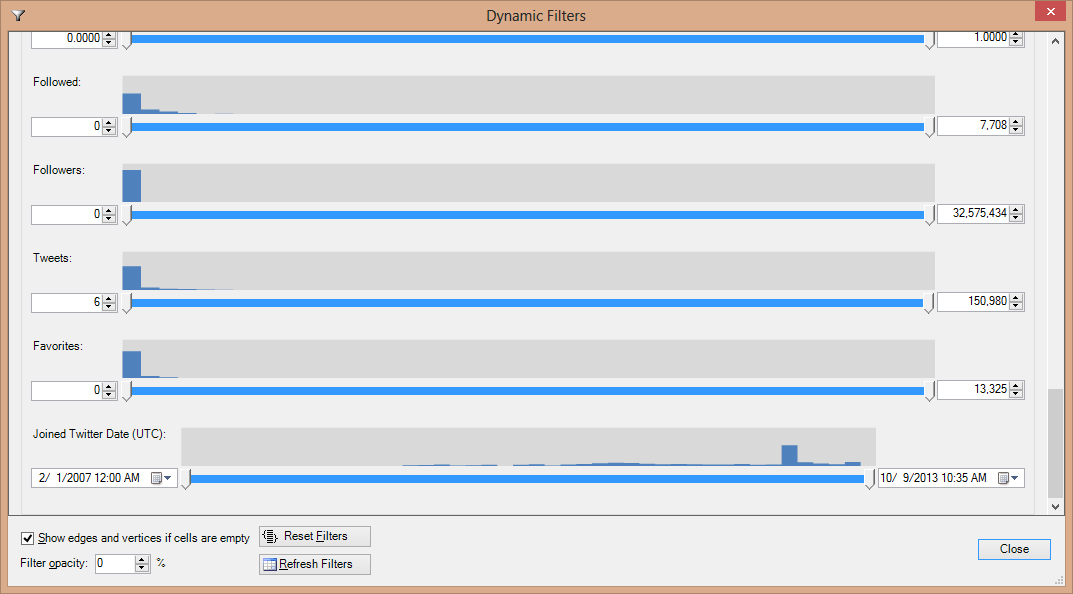

This is all the users that used the hashtag #azvote13 in the last day. Look at how many people opened a Twitter account on a few days in February of 2013.

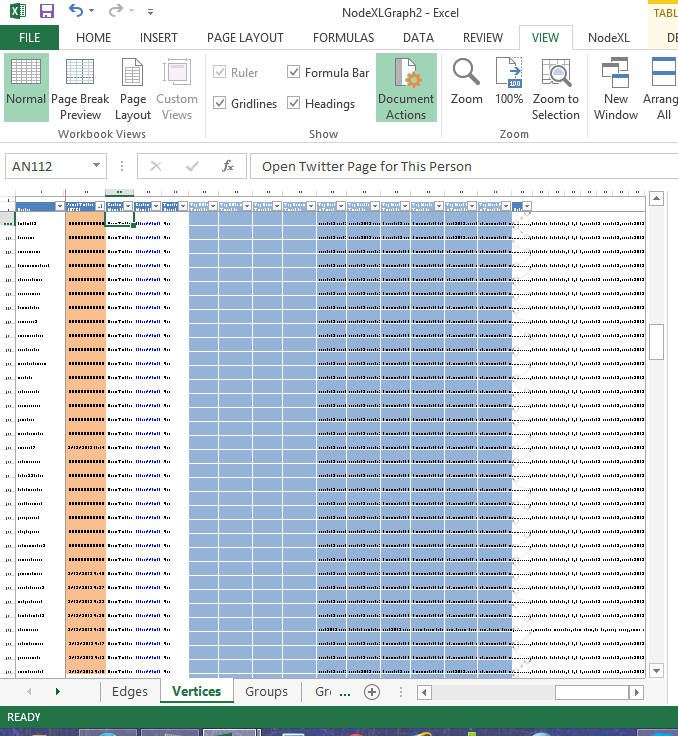

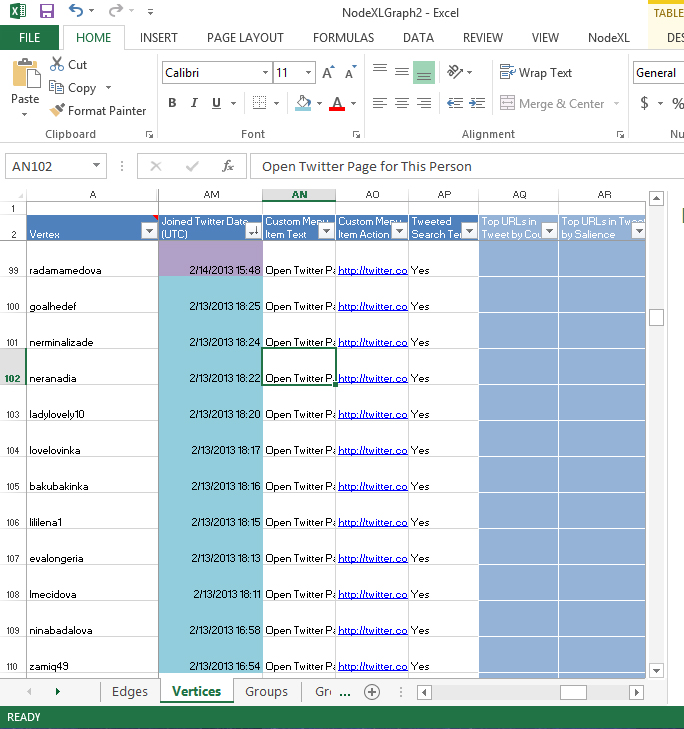

So I went to look at what was going on in those days in February. Not only were those accounts made on the same day, but they were made within minutes of each other. (If they’re highlighted the same color, it was the same day.)

So it is possible that there was some sort of training where a bunch of people created Twitter accounts at the same time, so I looked more closely at these accounts made in these days in February.

They generally follow the same few people. They generally don’t tweet a lot. Most haven’t tweeted a lot until this election period. I did a search on Facebook for some of them and no Facebook profile came up for them. It is possible that these young people spell their name differently on Twitter and Facebook – but in general I find that most young Azerbaijanis pick one way to spell their names on social media and stick with it.

So what were they tweeting about on the #azvote13 hashtag?

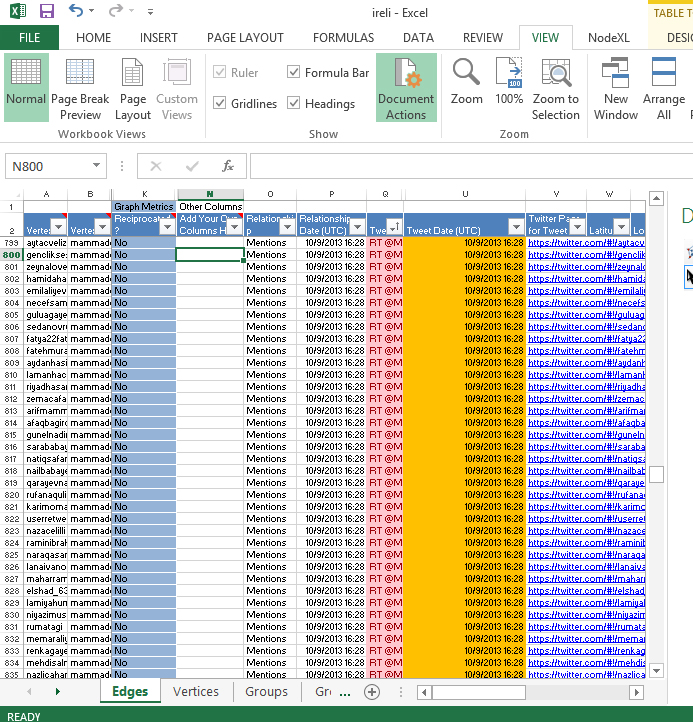

The same thing. The red/pink tweets are duplicates and the orange highlight is the same time. And they are at the exact same minute.

While it is theoretically possible for tweets to happen at the same minute, 100 tweets at the same minute by accounts all made in the same few days within minutes of each other? That’s a stretch.

What is interesting about this:

– this is way less detectible than buying fake Twitter accounts because the names are Azerbaijani, the profile pictures look like Azerbaijani people, even though there isn’t a lot of evidence that they are real.

– it is entirely possible that these are real people, but regardless, I speculate that one person has all the passwords and probably uses a particular app to send out the tweets at the same time.

– UPDATE 10PM BAKU TIME: I did a quick reverse image search on some of the profile photos of some of the profiles. The photos are ones that people can download and use all over the place. Here are some links and PDFs 1 2 3. And here are the original profiles.

– so, nice try – this was certainly more sophisticated than prior attempts, but still a FAIL.

As always, I’m happy to share these Excel files for people to look themselves.

We are young, heartache to heartache we stand; No promises, no demands #azvote13

Hashtags are an interesting 21st century phenomenon. Hashtags are keywords to organize information to describe a tweet and aid in searching (Small, 2011). Hashtags also take on a symbolic quality and perhaps are an example of metacommunication. When I post a picture of parents recording every minute of a kids’ holiday concert, complaining about how this is ruining the experience, I can add a hashtag #guilty to metacommunicate that I too participate in this. Symbolic use of hashtags also could be a way to show solidarity with some larger Internet community. When one sees a hashtag on a written sign at a rally, it shows some sort of connection to others that recognize the hashtag.

With that being said, analysis of a hashtag is much easier when there is a time-bound event like a rally or a protest, or in the case of this analysis, an election. When a hashtag is proposed for an event or topic, the intention is for a community of users to share information with each other. But hashtags also serve other purposes during an event: they can promote the event itself (come to the protest! #protest); they can give locationally situated information (the police are at the west gate #protest), and allow for live reporting that may send the message out to sympathetic others or media (Earl, McKee Hurwitz, Mejia Mesinas, Tolan, & Arlotti, 2013; Penney & Dadas, 2013).

For an election event in particular, a hashtag can serve as a means to share information, live report, and also to report possible fraud or violations. In the lead up to an election, a hashtag can be used for information dissemination.

With all that being said, hashtags also serve a boastful purpose. When a hashtag “trends” – it is noted by Twitter as being popular at a particular time. Users want a hashtag to trend to gain visibility and attention (Recuero & Araujo, 2012). While occasionally hashtags trend organically, it is much more common that hashtags are artificially pushed to the trending list (Recuero & Araujo, 2012).

This quantification of social media viability is very attractive. It allows a group to “prove” that it has a lot of support, even if it is artificial.

So, with that being said, let’s have a look at the hashtags for the 2013 Azerbaijani presidential election. (Here’s a pre-election report to give you a sense of the background).

A few different hashtags have emerged in the run up to the election. #azvote13 as well as #azvote2013, #secki2013, #sechki2013, and #besdir (the slogan of the main opposition candidate) are some of the most popular. I’ve been archiving #azvote13 and #secki2013 and #besdir for over a month.

It is important to note that pro-governmental forces have been engaging in some serious hashtag shenanigans all this year – hijacking hashtags thus rendering them useless for organizational purposes, amongst other things. However, in the past month or two, opposition youth have gotten more active on Twitter and seemed to take a stronger hold at different points recently. (Stronger hold = were the largest users of the hashtag.) There were a few alternative hashtags that emerged to make fun of a candidate, but overall the type of behavior that was seen earlier this year seems to have calmed down.

All this hashtag battling seems a little silly to me. But as noted before, hashtags are not just about being an information source, but about sending a signal. Thus, that tagging (to one’s own followers) is showing that “I’m talking about the election.”

Here’s some guidance on understanding these charts. One way to understand who a cluster is is to look at the links that they most frequently share and the source of those links. Are they tweeting from state news sources or opposition news sources, for example?

Here are the hashtags tracked over a long period of time:

#secki2013 – for the last month or so

The largest group of users of this hashtag were not connected to other people. But the second largest group was centered around opposition-leaning Hebib Muntezir (who has long been an information source for Azerbaijani news, lives outside of Azerbaijan, and currently works for an opposition-leaning sat/internet TV channel). Muntenzir’s following is quite interesting – the people around him aren’t heavily linked with each other. And they are receiving information from him, not vice versa – implying that he is an information source rather than a back-and-forth chatter.

Group 3 is the next largest group and it is the pro-government youth. They’re fairly interwoven with each other, and it centers on Rauf Mardiyev, the chairman of IRELI. You can see that his followers, like Muntenzir’s are a little distant from him. He is more a source of information than a chatter.

Group 4 is a very tight cluster – this is all the oppositionists. This is the first time that I’ve seen them all together in a cluster like this. Usually they subdivide into smaller clusters, but with links between them. There is a lot of communication between these people and a lot of efficient information sharing.

Group 5 contains the most active Twitter chatters of the opposition youth. They ended up in their own cluster probably because of how frequently they talk with each other.

#azvote13 – for the last month or so

The largest group here is the pro-government youth organization in Group 1. They’re pretty tight, although you can see some distant subclusters.

Group 2 is all the foreign media and NGOs that was covering the election as well as Azerbaijanis and foreigners that “affiliate” with these organizations.

Group 3 are the non-networked people.

Group 4 are the oppositionists and some media (usually when an opposition leader wrote a piece for a particular news organization and the tweet went out “@soandso’s article at @mediaorg”).

Group 5 is opposition youth – note the ties between group 4 and group 5.

Group 6 is muntenzir’s followers.

So what about election day itself?

#azvote13 for just election day

What’s interesting about election day itself isn’t so much the clusters as the content of what was tweeted – Lots of news coverage from every side. Also many instagram and Facebook photos of people voting, their ballots, and occasionally election violations.

—

So overall, Twitter is a battlefield. What is to be “won” is still not clear to me. I doubt this is a good use of anyone’s time to battle like this, but…

5pm Oct 9 hashtag update

More to come, but…

Group 1, the largest group, was unnetworked people.

Group 2 is a big cluster of foreign organizations and some individuals, Azerbaijani and foreign, associated with them. Seems like it was a lot of discussion and re-tweeting of Rebecca Vincent.

Group 3 is pro-government.

Group 4 is Azerbaijanis associated with the opposition.

Hashtags day before election

#azvote13 mid-September – October 8

Interesting changes here. Group 1, the pro-government forces, are a really tight cluster now. They used to be much less close. Seems like they’re talking to each other more now.

Group 3 is a VERY tight cluster of oppositionists. Strong ties exist between Group 3 and Group 4, centered around muntezir. Group 5 is foreigners and Azerbaijanis that hang out with foreigners.

#azvote13 October 2 – October 8

#azvote13 October 7 – October 8

#secki2013 October 2 – October 8

This is much less contentious than #azvote13.

10/15 talk: The reproduction and amplification of gender inequality online: The case of Azerbaijan

The reproduction and amplification of gender inequality online: The case of Azerbaijan

abstract:

Inequalities found offline are replicated and are often amplified online. Results from a nationally representative survey in Azerbaijan, an authoritarian post-Soviet petrostate with a tradition of gender inequality, demonstrates that being female is not only a barrier to Internet use, but the strongest barrier to Internet use, frequency, and capital-enhancing online activities. While this study cannot explain why being female has such an effect on access, use, and Internet activities, acknowledging the relative importance of can provide insight into potential targets or entry points for an intervention.

As part of the CHANGE seminar at UW.

10/15 12noon-1pm

Election week hashtag analyses

I’ll be continuing to monitor the hashtags, but here is where we stand on Monday morning before the Wednesday election:

#secki2013 for the weekend – pretty dead, but probably will pick up in the coming days

full analysis

#secki2013 for the past 10 days

full analysis

Opposition blogger muntezir is the most powerful tweeter in the network, but groups 3 and 4 are pro-government forces and are really loud on this hashtag.

#azvote13 for the weekend

full analysis

In this hashtag, the pro-government forces (group 2) are “winning” – being louder than the opposition forces. Although muntezir in group 4 and group 3 being a lot of oppositionists and their foreign friends are still holding strong.

#azvote13 since mid-September

full analysis

This tells a great story – while the pro-government forces (group 1) are very loud on this hashtag, all the other big clusters are very well connected and spreading information widely.

Social Networking Sites in Armenia – Facebook for Elites, Odnoklassniki for Everyone Else

(This is a continuation of a post I made in 2010 about this issue. This analysis based on the 2013 Alternative Resources in Media dataset.)

So, the social networking site that one spends time on isn’t arbitrary. Research tells us that generally people go where their friends are, but also that there are demographic differences in site choice. A study of MySpace versus Facebook in 2007 is the classic case of this. For a variety of reasons, wealthier and more educated people were on Facebook and poorer and less educated people were on MySpace. Nowadays in the U.S., Facebook has sort of taken over the social networking space and a lot of those demographic differences have gone away.

In the 2010 analysis posted above, Facebook in Armenia was quite elite while Odnoklassniki was not. Some reasons include that Odnoklassniki was more accessible on for free or cheap on mobile devices, the Russian language interface was more accessible to those without English skills (at the time Facebook was mainly an English language platform), Odnoklassniki was more about fun (and porn), and Facebook wasn’t great on a mobile device.

Fast forward to 2013, and things have changed. Facebook has grown a lot globally. The Facebook mobile platform is very user-friendly. Russian and Armenian versions of Facebook work quite well. More Armenians are online as well.

So I looked once again at use. Let’s first look at the overall picture before going into the demographic differences.

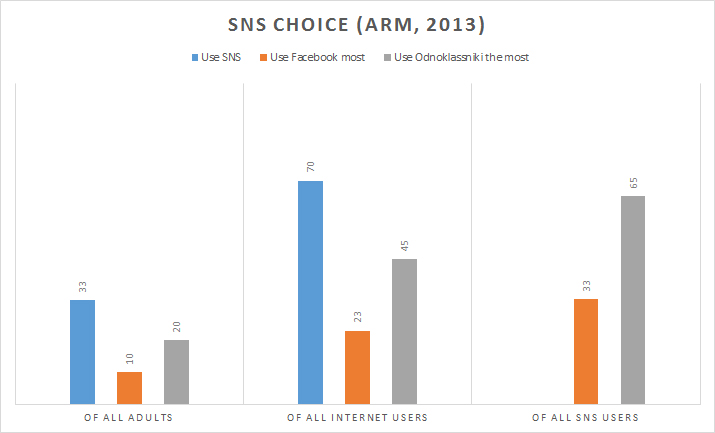

(Note that this is PRIMARY SNS, they could have accounts on the other site.)

First you can see that a third of all Armenian adults are on a social networking site and 70% of all adult Armenian Internet users are on a social networking site. The Odnoklassniki versus Facebook breakdown is that 10% of all Armenian adults are on Facebook, but 20% of all Armenian adults are on Odnoklassniki. Of Internet users, less than a quarter are on Facebook while nearly half (45%) are on Odnoklassniki. The comparative breakdown is a third of SNS users on Facebook and two-thirds on Odnoklassniki.

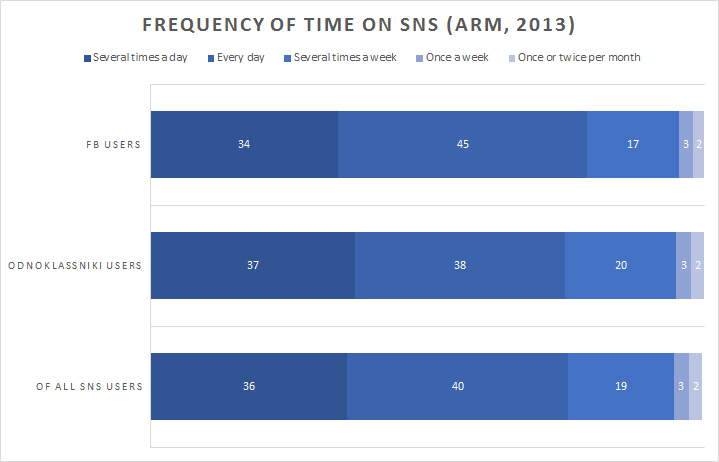

In terms of the time that is spent on the social networking site, there weren’t tremendous differences. About a third are on the SNS several times a day and most of the rest of the users are on the SNS at least once a day.

So who is on each site?

(This is based on an ANOVA):

There is no difference in age between Facebook and Odnoklassniki and other SNS users in AGE. However, non SNS users are much older. It is the same story with ECONOMIC WELLBEING – non SNS users are poorer than SNS users. The same is for RUSSIAN skills – the only difference is with non-SNS users and users.

ENGLISH skills – Facebook users (and other SNS users, but they’re weird, so let’s ignore them) have statistically significantly higher English skills than others.

Facebook users are also statistically significantly higher in EDUCATION than everyone else.

No differences in SEX.

So, we can summarize that Facebook users are more elite – English speaking and better educated. Thus, not a big chance from 2010.

(This is based on a multinominal logistic regression):

Looking at this 2013 data, the determinants of being an Odnoklassniki user are the following. In this analysis, all the different factors consider each other, so for example, the influence of higher education on English language skill is cancelled out, so each variable is really telling its own story.

First, Sex – men are more likely to be on Odnoklassniki than women. Next, Russian language skills – those with better Russian are more likely to be on Odnoklassniki than those with poor Russian. Then English skills matter. Then education.

Determinants of being on Facebook are first English skill. Better English means more likely to be on Facebook. Next, higher education. Russian language skill matters next.

For both Odnoklassniki and Facebook, age and economic status didn’t matter much. However, younger and wealthier people are more likely to be online. So it appears that once you’re online, your choice of social networking site is more about language skills and education.

So, with that, what are people doing on social networking sites?

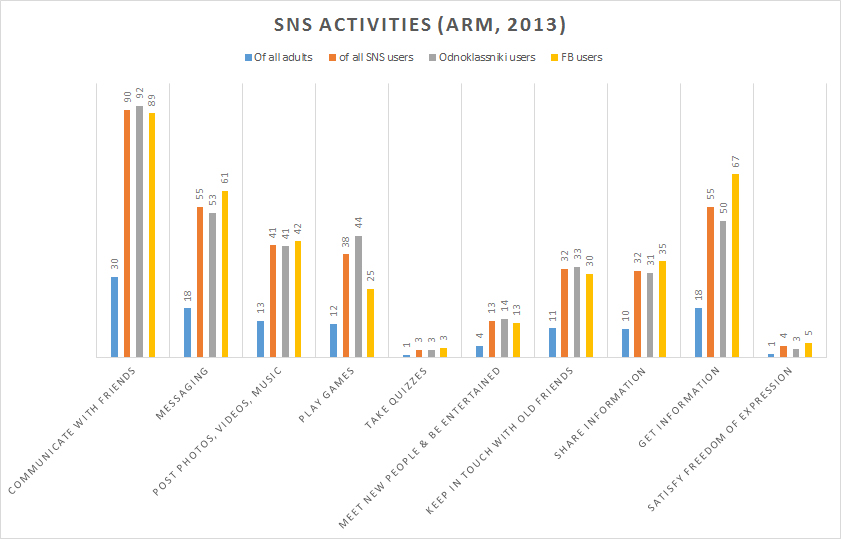

Remember that Facebook users are more “elite” – so the activities they do will likely be more elite as well.

In terms of communicating with friends, posting photos, and entertainment no big differences between the sites. However, Facebook users are more interested in getting and sharing information. Odnoklassniki users are also playing more games than Facebook users.

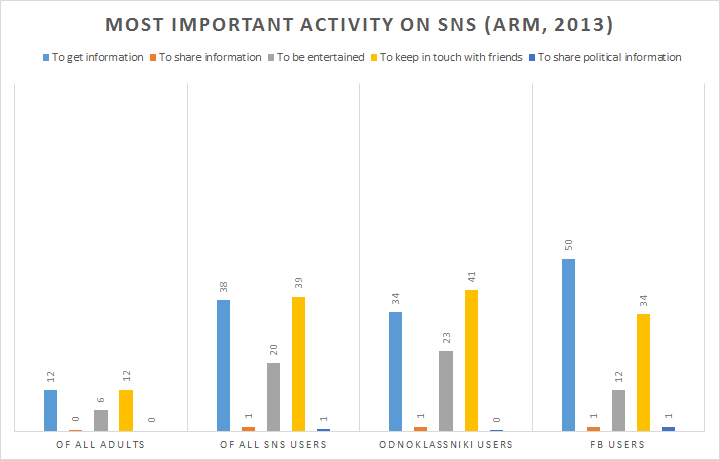

When asked what the most important activity on a social networking site, Facebook users were much more likely to say getting information.

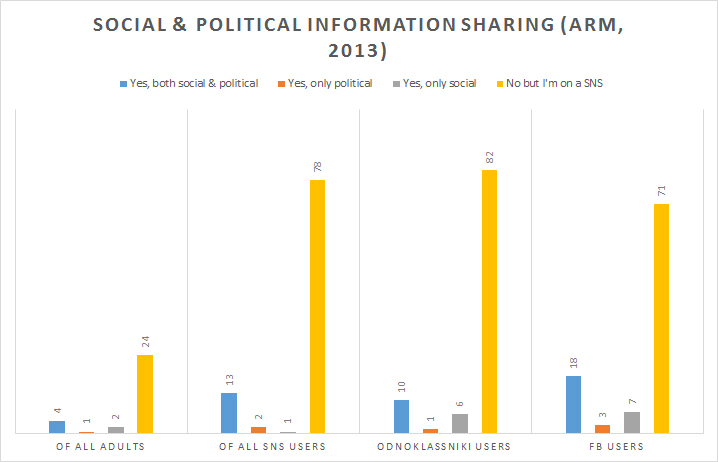

When asked about sharing political and social information, Facebook users are much more likely to share than Odnoklassniki users. But the majority of all social networking site users aren’t sharing (they say!).

Talk on 10/10: Maintaining scholarly distance, developing trust, and protecting sources online and offline in an authoritarian context

Pearce, K. E. (2013, October). Maintaining scholarly distance, developing trust, and protecting sources online and offline in an authoritarian context. Digital methods, ethical challenges: A symposium hosted by the Annenberg School Center for Global Communication Studies and the Project for Advanced Research in Global Communication, Philadelphia, PA.

Doing research in authoritarian states is not easy. While all research has challenges of access and credibility, with authoritarian states the hurdle height is raised. Yet academics tend to not talk about it (Goode, 2010) out of fear of losing access and credibility and because of the desire to do the research (Romano, 2006). Given that the “culture of fear” (Mitchell, 2002) in authoritarian states permeates every possible research method that is considered acceptable in traditional social science journals, researchers are left with few options.

With the development of increased information and communication technology, some scholars excitedly viewed the Internet as a way to access subjects in authoritarian states in a way that was not possible before the Internet. However, a whole additional host of challenges emerge when one uses the Internet to conduct research and when studying phenomena in authoritarian contexts, there are additional security and ethics concerns that are exacerbated by conducting research online. Yet the Internet does afford some benefits for research in this sort of environment, although researchers face new ethical questions that need to be addressed.

This presentation will detail some of the challenges and benefits of using the Internet for research in authoritarian states and what understanding ethical strategies in an environment where the wrong move can have grave impact can bring to the broader research community.

It is open to the public and a video will be available eventually.