Hashtags are an interesting 21st century phenomenon. Hashtags are keywords to organize information to describe a tweet and aid in searching (Small, 2011). Hashtags also take on a symbolic quality and perhaps are an example of metacommunication. When I post a picture of parents recording every minute of a kids’ holiday concert, complaining about how this is ruining the experience, I can add a hashtag #guilty to metacommunicate that I too participate in this. Symbolic use of hashtags also could be a way to show solidarity with some larger Internet community. When one sees a hashtag on a written sign at a rally, it shows some sort of connection to others that recognize the hashtag.

With that being said, analysis of a hashtag is much easier when there is a time-bound event like a rally or a protest, or in the case of this analysis, an election. When a hashtag is proposed for an event or topic, the intention is for a community of users to share information with each other. But hashtags also serve other purposes during an event: they can promote the event itself (come to the protest! #protest); they can give locationally situated information (the police are at the west gate #protest), and allow for live reporting that may send the message out to sympathetic others or media (Earl, McKee Hurwitz, Mejia Mesinas, Tolan, & Arlotti, 2013; Penney & Dadas, 2013).

For an election event in particular, a hashtag can serve as a means to share information, live report, and also to report possible fraud or violations. In the lead up to an election, a hashtag can be used for information dissemination.

With all that being said, hashtags also serve a boastful purpose. When a hashtag “trends” – it is noted by Twitter as being popular at a particular time. Users want a hashtag to trend to gain visibility and attention (Recuero & Araujo, 2012). While occasionally hashtags trend organically, it is much more common that hashtags are artificially pushed to the trending list (Recuero & Araujo, 2012).

This quantification of social media viability is very attractive. It allows a group to “prove” that it has a lot of support, even if it is artificial.

So, with that being said, let’s have a look at the hashtags for the 2013 Azerbaijani presidential election. (Here’s a pre-election report to give you a sense of the background).

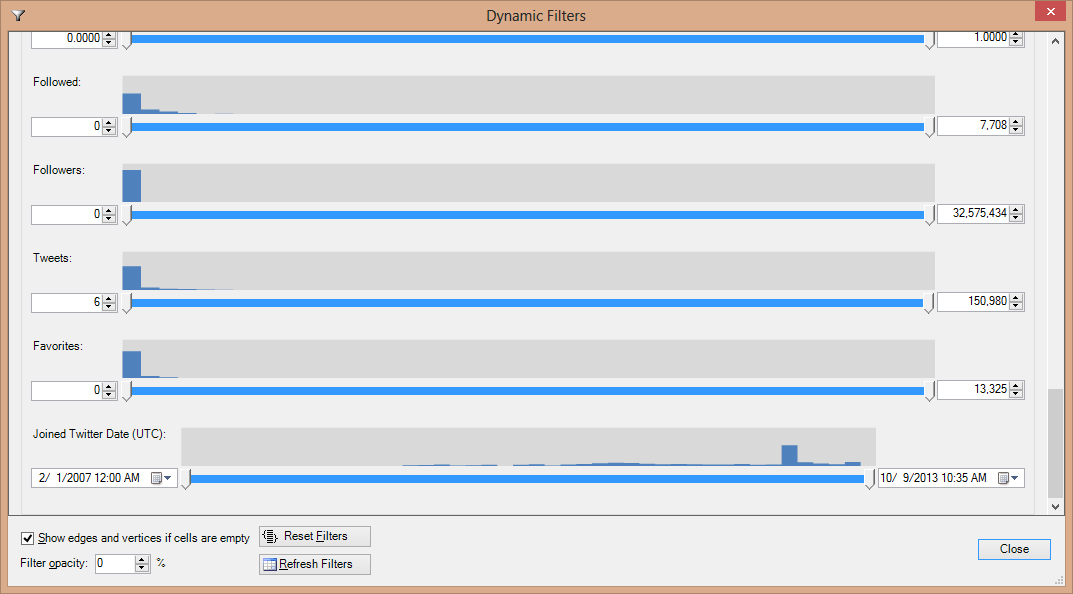

A few different hashtags have emerged in the run up to the election. #azvote13 as well as #azvote2013, #secki2013, #sechki2013, and #besdir (the slogan of the main opposition candidate) are some of the most popular. I’ve been archiving #azvote13 and #secki2013 and #besdir for over a month.

It is important to note that pro-governmental forces have been engaging in some serious hashtag shenanigans all this year – hijacking hashtags thus rendering them useless for organizational purposes, amongst other things. However, in the past month or two, opposition youth have gotten more active on Twitter and seemed to take a stronger hold at different points recently. (Stronger hold = were the largest users of the hashtag.) There were a few alternative hashtags that emerged to make fun of a candidate, but overall the type of behavior that was seen earlier this year seems to have calmed down.

All this hashtag battling seems a little silly to me. But as noted before, hashtags are not just about being an information source, but about sending a signal. Thus, that tagging (to one’s own followers) is showing that “I’m talking about the election.”

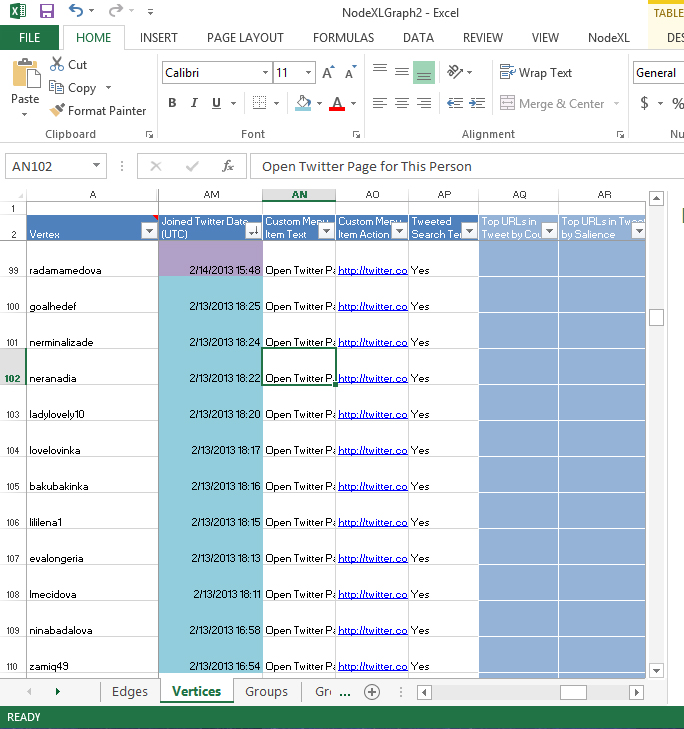

Here’s some guidance on understanding these charts. One way to understand who a cluster is is to look at the links that they most frequently share and the source of those links. Are they tweeting from state news sources or opposition news sources, for example?

Here are the hashtags tracked over a long period of time:

#secki2013 – for the last month or so

The largest group of users of this hashtag were not connected to other people. But the second largest group was centered around opposition-leaning Hebib Muntezir (who has long been an information source for Azerbaijani news, lives outside of Azerbaijan, and currently works for an opposition-leaning sat/internet TV channel). Muntenzir’s following is quite interesting – the people around him aren’t heavily linked with each other. And they are receiving information from him, not vice versa – implying that he is an information source rather than a back-and-forth chatter.

Group 3 is the next largest group and it is the pro-government youth. They’re fairly interwoven with each other, and it centers on Rauf Mardiyev, the chairman of IRELI. You can see that his followers, like Muntenzir’s are a little distant from him. He is more a source of information than a chatter.

Group 4 is a very tight cluster – this is all the oppositionists. This is the first time that I’ve seen them all together in a cluster like this. Usually they subdivide into smaller clusters, but with links between them. There is a lot of communication between these people and a lot of efficient information sharing.

Group 5 contains the most active Twitter chatters of the opposition youth. They ended up in their own cluster probably because of how frequently they talk with each other.

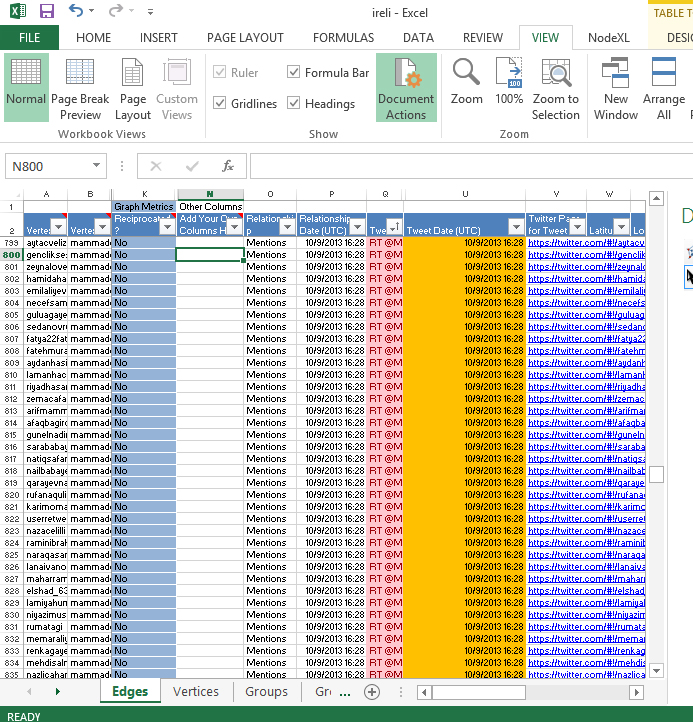

#azvote13 – for the last month or so

The largest group here is the pro-government youth organization in Group 1. They’re pretty tight, although you can see some distant subclusters.

Group 2 is all the foreign media and NGOs that was covering the election as well as Azerbaijanis and foreigners that “affiliate” with these organizations.

Group 3 are the non-networked people.

Group 4 are the oppositionists and some media (usually when an opposition leader wrote a piece for a particular news organization and the tweet went out “@soandso’s article at @mediaorg”).

Group 5 is opposition youth – note the ties between group 4 and group 5.

Group 6 is muntenzir’s followers.

So what about election day itself?

#azvote13 for just election day

What’s interesting about election day itself isn’t so much the clusters as the content of what was tweeted – Lots of news coverage from every side. Also many instagram and Facebook photos of people voting, their ballots, and occasionally election violations.

—

So overall, Twitter is a battlefield. What is to be “won” is still not clear to me. I doubt this is a good use of anyone’s time to battle like this, but…

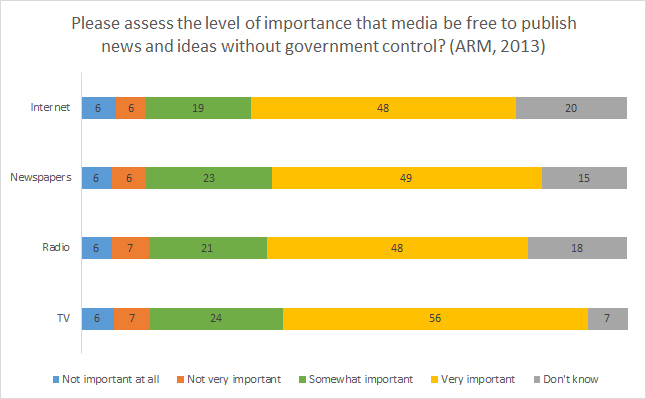

(Via Civilnet.am)

(Via Civilnet.am)