Tag Archives: azerbaijan

Hashtags day before election

#azvote13 mid-September – October 8

Interesting changes here. Group 1, the pro-government forces, are a really tight cluster now. They used to be much less close. Seems like they’re talking to each other more now.

Group 3 is a VERY tight cluster of oppositionists. Strong ties exist between Group 3 and Group 4, centered around muntezir. Group 5 is foreigners and Azerbaijanis that hang out with foreigners.

#azvote13 October 2 – October 8

#azvote13 October 7 – October 8

#secki2013 October 2 – October 8

This is much less contentious than #azvote13.

Election week hashtag analyses

I’ll be continuing to monitor the hashtags, but here is where we stand on Monday morning before the Wednesday election:

#secki2013 for the weekend – pretty dead, but probably will pick up in the coming days

full analysis

#secki2013 for the past 10 days

full analysis

Opposition blogger muntezir is the most powerful tweeter in the network, but groups 3 and 4 are pro-government forces and are really loud on this hashtag.

#azvote13 for the weekend

full analysis

In this hashtag, the pro-government forces (group 2) are “winning” – being louder than the opposition forces. Although muntezir in group 4 and group 3 being a lot of oppositionists and their foreign friends are still holding strong.

#azvote13 since mid-September

full analysis

This tells a great story – while the pro-government forces (group 1) are very loud on this hashtag, all the other big clusters are very well connected and spreading information widely.

Honor and Death: Is the Internet Exacerbating Suicide in Azerbaijan?

September 10 is World Suicide Prevention day.

The most recent data on suicide in Azerbaijan is from 2007. However, according to this (iffy) website, suicide is the 20th most common cause of death in Azerbaijan, with over 400 each year.

In an informal analysis of Azerbaijani news stories, I came up with 6 young female suicides or attempts in 2013 and 4 in 2012. Obviously, this is not an official count. [Link to reports]

Why so many suicides and attempted suicides of teenage and young women?

In Kazakhstan there has been a lot of teenage suicides as well. Recently there were suggestions that information overload and the current media environment is causing the suicides in Kazakhstan.

But what of Azerbaijan? In a piece that I’m working on right now about Internet gender inequality in Azerbaijan, I speculate that these extreme measures – i.e. suicide attempts – are because of Azerbaijan’s honor culture.

An honor culture is is one that uses specific behavior codes to which members of the culture must obey. Upholding and defending the reputation of one’s self and family is paramount. This honor serves as a structure of social power and discipline. If someone else violates someone’s honor, a response or retaliation is required. In honor cultures, women are modest, have a norm of shame, and avoid behaviors that may embarrass their family. A failure to maintain honor harms their and their family’s reputation. Men, on the other hand, have to constantly prove their manhood as social status. Research shows that individuals in honor cultures are more vulnerable to suicide because of social isolation and feelings of being a burden to the family. For women especially, suicide may be the only way to restore family honor and remove shame.

In this paper, I argue that the Internet may be making female honor more complicated in Azerbaijan. Blackmailing women with honor-related overtones is something that happens for both public figures (like Khadija Ismayilova, a frequent target of honor-related shaming), as well as regular Azerbaijani women who become victims of blackmail attempts.

Recently I was made aware of one of these situations. A young woman was filmed doing a (somewhat) erotic dance. At BEST she looked extremely uncomfortable. At worst she appeared to have been drugged. It was painful to watch. I can imagine exactly what happened. Her boyfriend said, “Hey, can I film you with my phone so I can watch later? (While in the army? At home?)” She didn’t want to. Maybe she told him she didn’t want to, maybe she didn’t. But he suspected her reluctance and said, “Don’t you trust me?” What is a young Azerbaijani girl supposed to answer to that? “No, I don’t trust you. Do not film me.” — That would be impossible. So she let him film her.

Weeks or months later, for whatever reason, they broke up. Maybe he threatened her with making the video public. Maybe he just put it online. Regardless, it make it online.

Soon after, she attempted suicide.

While it is impossible to blame these suicides and attempts on “the Internet,” given Azerbaijan’s honor culture, the Internet and social media’s attributes that are usually highlighted as assets (ease of low-cost creation and distribution, for example), are also the same attributes that make bullying possible as well.

I wish that I had a way to help these young women — not let themselves be filmed or photographed in the first place, perhaps? But helping young women play defense is not going to resolve this issue. What is a realistic approach to reduce suicides? How can Azerbaijani women be encouraged to go online when the possibility of this sort of personal blackmail exists?

I’ll be thinking about these questions, in light of World Suicide Prevention Day, and I hope you will as well.

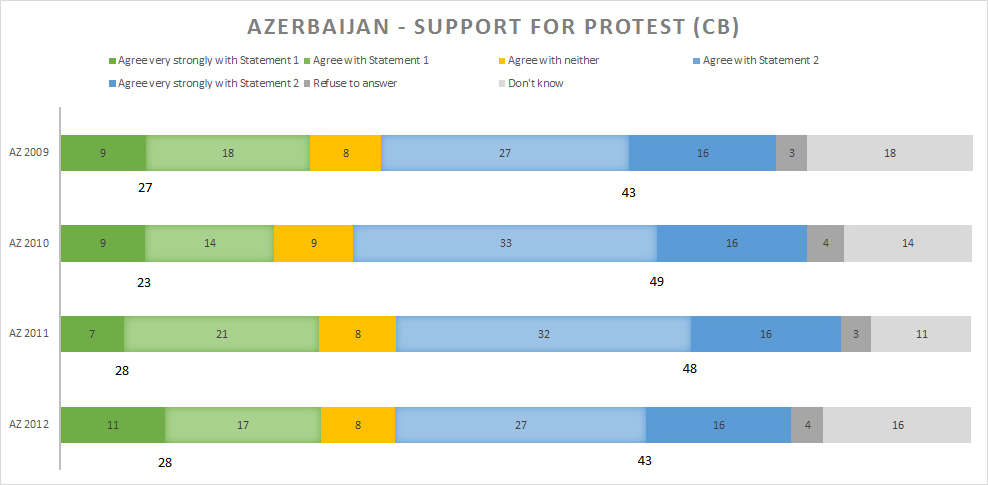

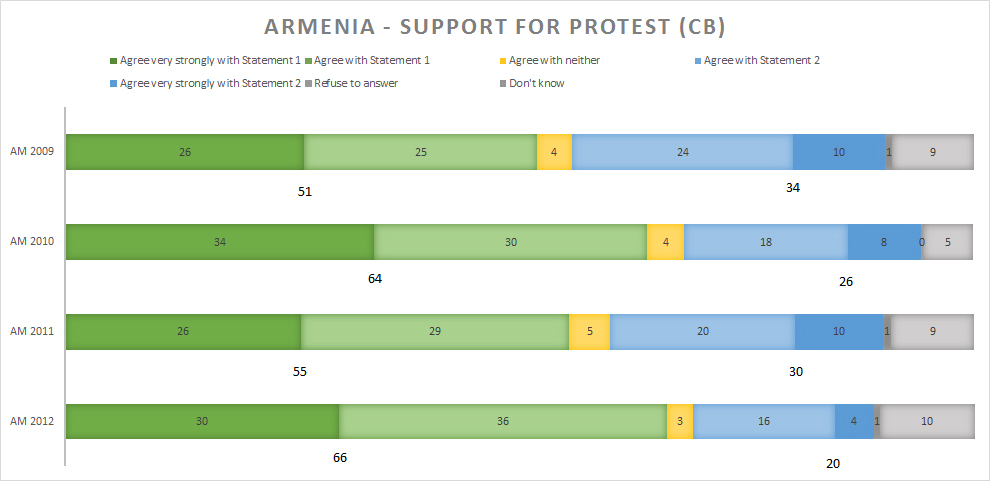

Attitudes toward protest over time

(I did a quick blog post on this earlier this year, FWIW)

Attitudes toward protest is one of my favorite Caucasus Barometer questions.

(Sarah Kendzior and I wrote a piece centered around this measure in 2012).

It is an interesting way to ask a question in a vignette format.

People are asked which statement they agree with and degree.

* Very much agree: People should participate in protest actions against the government, as this shows the government that the people are in charge.

* Agree: People should participate in protest actions against the government, as this shows the government that the people are in charge.

* Neither

* Agree: People should not participate in protest actions against the government, as it threatens stability in our country.

* Very much agree: People should not participate in protest actions against the government, as it threatens stability in our country.

* Don’t know

And of course they can refuse to answer.

statement 1:

People should participate in protest actions against the government, as this shows the government that the people are in charge.statement 2:

People should not participate in protest actions against the government, as it threatens stability in our country.

Wow – Georgia in 2012 was really interesting. Of course the Caucasus Barometer was collected in the middle of a huge election, so this likely explains the jump from a stable one-third to over half supporting people protesting in one year.

Attitudes toward protest in Azerbaijan are fairly stable, with about a quarter of the population thinking that it is okay to protest and 43-49 percent thinking that it is not okay. The “don’t knows” and “refuse to answer” are pretty high in Azerbaijan — which could reflect fear, masking, or ignorance.

Between half and two-thirds of Armenians feel that protest is a good thing. And between 20-34 percent of Armenians don’t think that people should protest. A pretty low percentage had no opinion in the matter. The Caucasus Barometer is collected in the late fall. With the 2008 presidential election issue and the early 2013 presidential election issue, during which some protesting occurred, one must wonder if these protests and the response to them had an effect on public opinion.

—–

I was curious who these supporters and non-supporters are (I only did this on the 2012 data).

Armenians that refused to ansawer were highly educated and more urban.

Armenians that answered “don’t know” were wealthier.

Armenians that supported protests were wealthier and more interested in discussing politics.

However, Armenians that didn’t support protests were also wealthier and more interested in discussing politics.

Azerbaijanis that refused to answer were more urban, frequent Internet users, and wealthier, as well as more likely to discuss politics with friends.

Azerbaijanis that said that they didn’t know were more rural and wealthier.

Azerbaijanis that supported protests were more urban, more likely to discuss politics, and wealither, as well as female.

Azerbaijanis that didn’t support protests were also more urban, wealthier, and discuss politics.

In Georgia, those that support protest are more urban, better educated, and more willing to discuss politics.

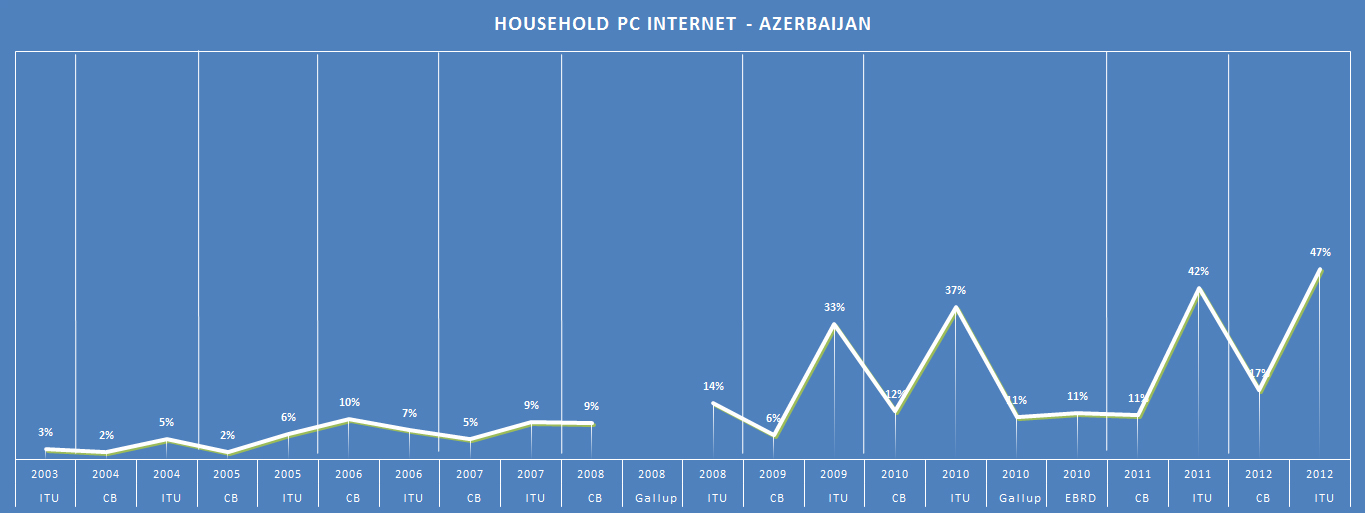

Let’s have a data party

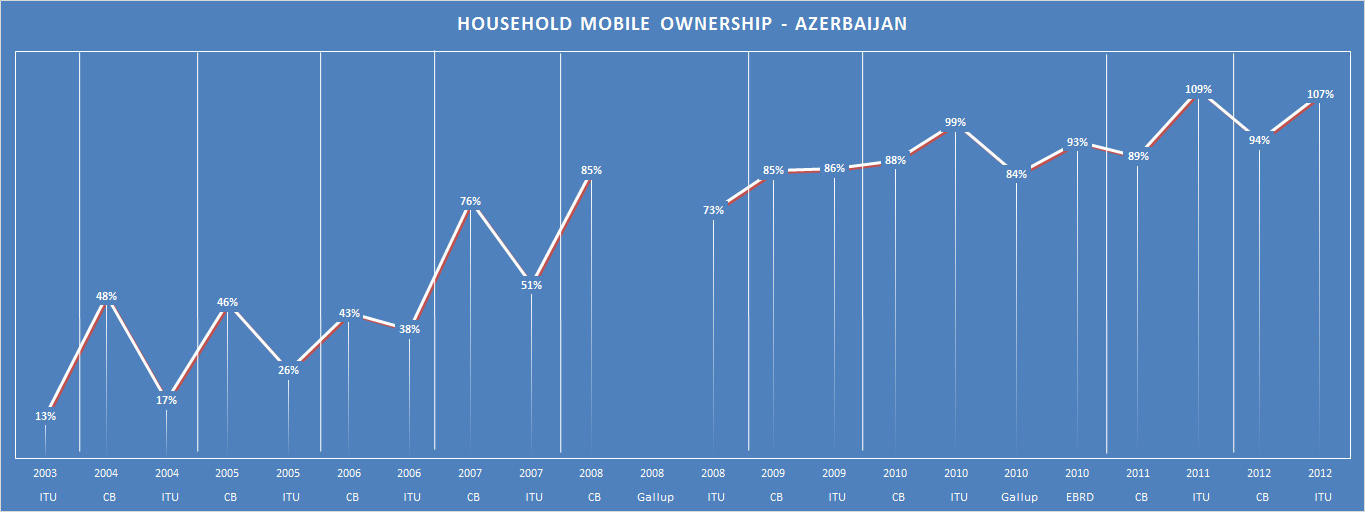

Last year I wrote a blog post about triangulating different data sources. I used the example of mobile phone ownership and the ITU, Caucasus Barometer, and Gallup. In that post I said:

“The point I’d like to make is that these statistics are complicated and it is hard to get at the “right” number. That’s why we try to triangulate — look at different sources of data to see if things seem right. We also should always assess the credibility of the source of the data.

Data sources:

ITU is the UN’s official statistics and these numbers come from the governments themselves who usually get the numbers from the telecommunications companies. These companies count number of SIM cards sold and it is not unusual for people to have multiple SIM cards. This is data to be highly skeptical about. For the question about mobile penetration, this isn’t actually percent, it is number of mobile phones per 100 people.

Caucasus Barometer, Gallup, and EBRD are surveys taken face-to-face in households. All use different sampling techniques and are collected by different organizations. None are perfect, but they’re as good as we’ve got. Of the three, I trust Gallup the least.

Noteworthy:

All of these were collected at different times of the year.

Margin of error varies in all of these.

A ~4-6 point difference is within the margin of error and shouldn’t be looked at with too much suspicion.”

With those same rules applying, here are some results from different sources from Azerbaijan.

For what it is worth, I LOVE having more data. The more data we have measuring similar things, the more sure we can be of the results. 2010 is a great year here because of the 4 data sources (for some questions). But please, reach your own conclusions about what the “correct” percentage is.

PPS, here is a similar comparison of Armenia’s statistics from a few years ago. And here’s one for Armenia specifically on mobile comparison.

Ten thousand signatures felt like ten thousand hands, they carry me

An online petition has been recently been circulating through Azerbaijani Internet circles asking people to support freeing youth activists who have been arrested in 2013, in light of the October 2013 presidential election.

As of early August, 2000 people have signed. (The hashtag suggests they need 10,000 signatures.)

I’m pretty meh about online petitions, although I have recently changed my tuned, as they do provide evidence for “citizen support” in Azerbaijan where public opinion is difficult to ascertain.

Regardless, I’ve done a hashtag analysis of the efforts on Twitter.

Only July 31 when the campaign began, this was the hashtag map.

Popular Azerbaijani Internet personalities Habib Muntezir and Bakhtiyar Hajiyev each have their own clusters of followers and retweeters. The youth organization N!DA (from whom many of the detained activists come) and its leadership make up the largest cluster though.

I did another analysis on August 5 and things look a little different.

Now those key users (Muntezir, Hajiyev, and the official Twitter account of N!DA) from the first analysis are all in cluster 1 together. Cluster 2 includes the leadership of N!DA, separate from the official N!DA account. My guess is that those individuals associated with N!DA are communicating with each other, perhaps about other things, more frequently than they are with the rest of the network, so they have become clustered together.

I don’t entirely understand clusters 3 and 4. Cluster 3 includes some foreigners who tweet about Azerbaijan (including myself). Suggestions on this are welcome.

—

In my estimation, a lot more of the discussion of this issues takes place on Facebook rather than Twitter. However, analysis of Facebook hashtags is slow in coming.

Do they even know his name?

The Azerbaijani opposition has cooperated and agreed upon (for now) a single candidate for the upcoming presidential election: Rustam Ibragimbekov. Ibragimbekov (Ibrahimbekov /Ibrahimbeyov / Ibragimbeyov) is a 74-year-old screenwriter, best known for winning an Oscar for the (awesome) 1995 film “Burnt by the Sun.” (Well, it won best foreign film, so he shared the award.)

Despite residing in Moscow (and LA?), he has been involved on the fringe of Azerbaijani politics. Perhaps “on the fringe” simplifies his role, but certainly he isn’t involved in the day-to-day politics. You can read more about this in the Wikipedia article linked above.

One question that I have is — do regular Azerbaijanis know who Ibragimbekov is? He certainly is well known in intellectual circles, but I have no idea if the average rural Azerbaijani recognizes his name. Was he lauded during the Soviet period?

A government spokesman even said (in late July 2013) “If Rustam Ibrahimbeyov thinks that the entire Azerbaijani society must be grateful to him for a couple of films, this is the wrong position.”

So I went back into the foreign and US news archives to see if I could determine news coverage about Ibragimbekov. Here are PDFs of the news archives if you want to check it out for yourself. articles1 articles2 articles3 articles4 articles5 EBSCOhost LNtotalenglish LNtotalforeign LNbroad

In the 1980s and early 1990s Ibragimbekov popped up in the American news when there were occasional joint Soviet-American film projects. He was head of an association that worked on joint projects and would comment on the efforts.

In the 2000s he had a few films that premiered on the international circuit and reviews appeared in some American newspapers.

In 2004 he made some statements about NK, apparently to the BBC. Here is a report on this from ArmInfo.

ARMINFO NEWS AGENCY

May 21, 2004

SOLUTION TO PROBLEM BY FORCE METHODS IN 20TH AND 21ST CENTURIES IS A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY: AZERBAIJANI WRITERBAKU, MAY 21. ARMINFO. Even if the Armenian party manages to prove that historically, politically etc…, Nagorny Karabakh must be separated from Azerbaijan, a solution to the problem by force methods in the 20th and 21st centuries is a crime against humanity, on the whole, said a well-known Azerbaijani writer Rustam Ibragimbekov in his interview to BBC.

He said that in this case the question is not the conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijanis. Thus, the World War I started with a shot by a student. On the one hand, Azerbaijan has lost must because of the conflict. on the other hand, Armenia loses much because of the economic blockade i.e. because of the conflict. Armenians are known to be very enterprising people, professionals, and now, if they were engaged in the economic and financial processes in Azerbaijan, it would have brought a great benefit both to Azerbaijan and them. Being part of Azerbaijan is more advantageous for them than being part of Armenia, as Azerbaijan means oil, great business potential, and Armenians are potential businessmen, the writer said.

He also said that Armenians residing in the territory of Azerbaijan before, entered the common career circulatory system. In 30s and 40s of the XX century. everything was so exact. a man worked in Karabakh, then he moved to Baku and then to Moscow. A usual state-party career stairs. But at a definite moment, the Karabakh residents felt that their move upstairs in Azerbaijan was slackened, as many local national cadres occured who competed with them. Armenia, in its turn, did not accept Karabakh residents as they were member of the Azerbaijani party-organization. The enterprising people, every one of the one hundred of thousands of the people, faced a deadlock and wanted to get separated, Ibragimbekov said.

And also from ArmInfo in 2004:

ARMINFO NEWS AGENCY

May 21, 2004

AS A WORLD CITIZEN I GIVES BOTH PARTIES THE RIGHT TO NAGORNY KARABAKH, BUT THIS CONFLICT MUST NOT BE SOLVED BY FORCE METHODS: AZERBAIJANI WRITERBAKU, MAY 21. ARMINFO. “In connection with Karabakh conflict, Baku lost wonderful Baku citizens, several hundreds of thousands of perfect specialists loving Azerbaijan and Baku (I mean Armenians) who had to leave the country,” said a well-known Azerbaijani writer Rustam Ibragimbekov in his interview to the BBC.

It is noteworthy that Ibrigimbekov is the scenarist of the Soviet masterpiece of movie “The Desert White Sun,” as well as the films, the winner of grand prizes of the Cannes Movie Festival in Venice, his another film “Tired of Sun” won Oscar.

He refuted the information that Azerbaijan Mass Media has activated the campaign on creation of an image of the enemy in the person of Armenians. He said that the current developments are just a feeling of despair, which gradually embraces the Azerbaijani residents. And it is justified as “we constantly wait for the word community to interfere into this conflict more actively.” “Besides the Karabakh problem, there are 7 occupied territories of Azerbaijan bearing no relations to Karabakh. However, they are seized. If this issue is partially solved on the basis of some compromises, naturally, it would considerably change the attitude of Azerbaijanis to the conflict. Everything would be much easier,” Ibragimbekov said.

He said that if those who was in a hurry to settle the conflict at the end of 80s had a little patience, “we would have got more simple resolution, less bloody and painful for the both parties.” As a world citizen he gives both parties the right to Nagorny Karabakh, but thinks that this conflict must not be solved by force methods.

In 2008 Ibragimbekov made a few statements criticizing the Azerbaijani government. This RFERL article is probably worth reading.

Azerbaijani Director Demonized For Comments On National Elite

Government Press Releases (USA) – Tuesday, November 18, 2008

More than last month’s utterly predictable presidential ballot, more even than the November 2 meeting in Moscow between the presidents of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Russia, a recent interview by the acclaimed Moscow-based Azerbaijani writer and film director Rustam Ibragimbekov has galvanized and polarized Azerbaijan’s political elite and intelligentsia.The brief interview was published by pravda.ru in late October. Asked whether the situation in Baku today is “better” than before the demise of the USSR, Ibragimbekov deplored what he termed a “demographic catastrophe” that has completely transformed the city’s population. He pointed out that of a population of 1.5 million, approximately half — mostly Azeris — have left, and they have been replaced by 2 million newcomers who “are not ready for urban life.”

As a result, Ibragimbekov continued, Baku, which used to have its own lifestyle and outlook on life, has become a totally different city, although “a few outposts” of the old mentality still survive. And even more crucially, what he referred to as the “national elite” has been largely destroyed, and its few surviving representatives sidelined. The very mechanism for sustaining such an elite has been destroyed, Ibragimbekov continued. And in a country without a true national elite, those who rise to positions of power and authority do so not on the basis of their abilities, but thanks to family or regional ties, or financial clout.

Azerbaijan’s parliament scheduled an emergency debate on Ibragimbekov ‘s interview on October 30. In its virulence and vindictiveness, the debate was chillingly reminiscent of Soviet-era intolerance of dissent. One deputy after another accused Ibragimbekov of lacking patriotism or seeking to split the nation. For example, Yagub Mahmudov, the director of the Institute of History of Azerbaijan’s Academy of Sciences, denounced the interview as an insult to the entire Azerbaijani nation, and in particular to the intelligentsia. He declared that if pravda.ru had distorted what Ibragimbekov actually said, he should disavow the interview, and that if he was quoted accurately, he should apologize.

Not a single deputy spoke out during the debate in Ibragimbekov ‘s defense, although indefatigable oppositionist Panah Guseinov commented that if Ibragimbekov had the current parliament in mind when he spoke of persons who rose to authority despite their lack of abilities, his observation was correct. But some deputies from the ranks of the intelligentsia reportedly admitted privately that they considered the vilification of Ibragimbekov excessive.

By contrast, opposition politician Lala-Shovket Gadjiyeva lauded Ibragimbekov in a November 1 interview with day.az as “a true patriot,” and argued that the parliament deputies’ collective reaction only serves to underscore that “the tradition of exerting pressure on successful, honest, worthy people still survives…. We have never valued our intelligentsia,” but always sought to destroy its finest representatives, Gadjiyeva said.

Echoes of the Soviet Era

Journalist Ramiz Abutalybov on November 3 compared the verbal attacks on Ibragimbekov to the 1930s denunciations of Mamed Emin Rasulzade, leader of the short-lived Azerbaijan Democratic Republic from 1918-20, as an “enemy of the people,” and to the later vilification of acclaimed Soviet Russian writers Boris Pasternak and Alexander Solzhenitsyn by people who had never read a word they wrote.

The creative intelligentsia, meanwhile, rallied to Ibragimbekov ‘s defense: a total of 286 people signed a statement affirming Ibragimbekov ‘s right to express his views and criticizing the parliament reaction as “an alarming symptom of our lawmakers’ low [level of] political culture,” day.az reported on November 7.

Echoing George Bernard Shaw, Ibragimbekov told day.az on October 31 that while he does not share his critics’ assessments, he respects their right to express them. He also confirmed that his original statements were not distorted, although he said they were shortened in a way that slightly changed the original emphasis. And he said he sees no reason to apologize.

But in a November 3 interview with RFE/RL’s Azerbaijani Service, Ibragimbekov was more categorical, affirming that parliament deputies demonstrated “political illiteracy” by convening a debate on his interview without taking into account the political implications of doing so. “The parliament session was a direct refutation of [the existence of] freedom of speech in Azerbaijan.”

At the same time, Ibragimbekov stressed to RFE/RL that he did not mean to imply in his pravda.ru interview that the present Azerbaijani leadership is composed entirely of mediocrities.

While much of what Ibragimbekov said in that interview is valid, two aspects of his jeremiad nonetheless require qualification. He fails to mention that the eclipse of Baku’s reputation as a cosmopolitan, sophisticated, and tolerant city began before the collapse of the USSR, with vicious reprisals against Armenians in 1988 in retaliation for the campaign initiated by the oblast soviet of the then-Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast for the enclave’s unification with the then-Armenian SSR. Many Armenian families fled Azerbaijan at that time in fear of their lives.

And Ibragimbekov ‘s warning that in a country devoid of a national elite, connections and money, rather than ability, become the key to a successful career does not encompass the counterargument that during the Soviet era, membership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and public adherence to the party line were the sine qua non for advancement.

RFE/RL

In 2013 the articles are primarily about Ibragimbekov as a candidate.

…..

I wasn’t able to find any coverage of Ibragimbekov in the mainstream Azerbaijani press. That doesn’t mean that there wasn’t ever any coverage, but there aren’t any records of it. It’d be great to get a better sense of the people’s knowledge of this man. I don’t think that these news sources are going to answer my question though.

Update to Azerbaijan tech trends slideshow

Here’s a 2012 update to this slideshow.

Voting – 2012 version

By requests, let’s look at voting behaviors in the 2012 Caucasus Barometer.

Do Caucasians think that it is important for a good citizen to vote?

With three-quarters of Georgians believing that it is extremely important for a good citizen to vote (mean 8.74/10), and less than two-thirds of Armenians (8.37/10) and half of Azerbaijanis believing so (7.82/10), the emphasis on voting in Georgia is clear.

Would you vote in a presidential election on Sunday?

The most interesting thing here is the lack of Azerbaijani enthusiasm for voting.

With regard to the fairness of elections…

Georgia is the “winner” here with over half of Georgians feeling like their last election was completely fair. (This was a November 2012 poll, BTW.) Azerbaijanis have a high don’t know.

2010 version of this here – many more interesting questions in that year!