Tag Archives: azerbaijan

Baby Makin’ in the Caucasus

There are a number of initiatives to try to increase the number of babies born in the Caucasus.

But how many kids do people want?

It seems that Armenians, Azerbaijanis, and Georgians have very different feelings on this question.

Also noteworthy is that only in Armenia do women and men see things differently.

But there certainly is a regional component to this.

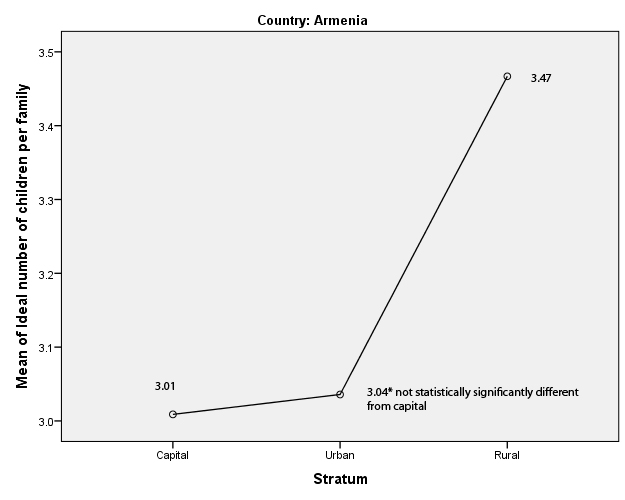

Armenians in Yerevan and regional cities only want about 3 kids, while rural Armenians on average want 3.47 (obviously not .47 of a child!)

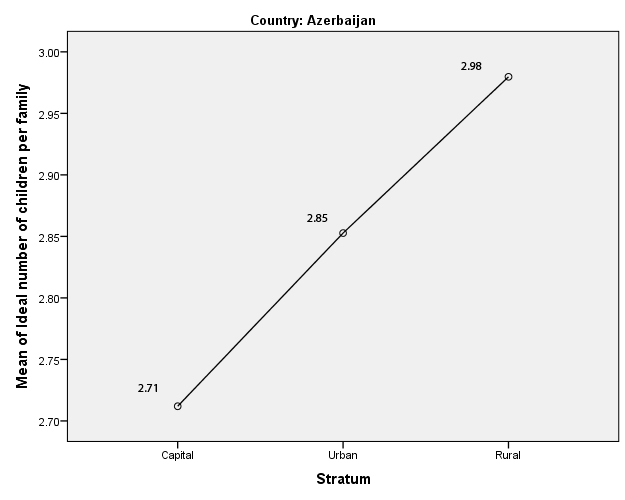

In Azerbaijan, there is a straight line from Baku, to regional cities, to rural people. But it is fair to say that Azerbaijanis mostly want about 3 kids.

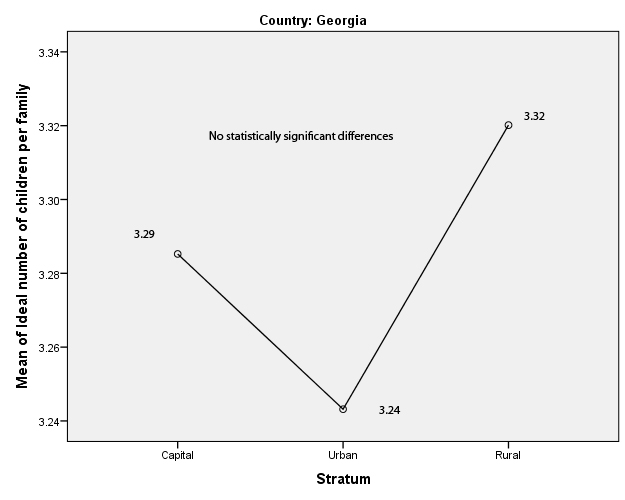

Georgians, on average interested in having more than 3 kids, don’t differ regionally.

For other analysis on babies in the Caucasus, check these posts:

#ismayilli hashtag analysis Jan 27 – Feb 4

Ismayilli isn’t “over,” at least on Twitter.

What is really interesting about this updated analysis is the exceptionally tight cluster in group 1 – full of foreign NGOs and news organizations as well as English-tweeting Azerbaijanis and group 2 is again strange with all of these non-profile picture accounts.

The tweets themselves are mostly retweets of news stories.

Low level corruption in the Caucasus

While corruption is without a doubt a major issue in the Caucasus, many think about higher level corruption rather than day-to-day corruption.

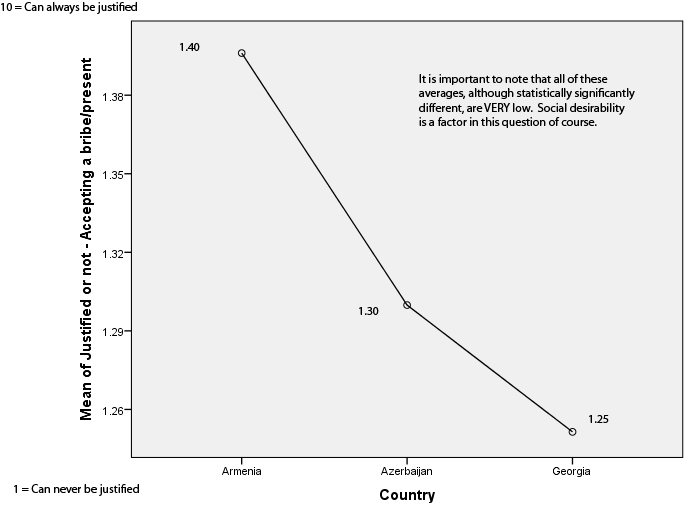

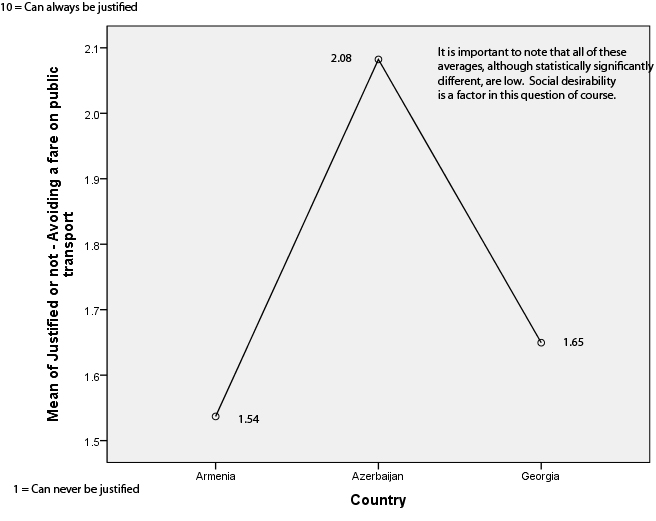

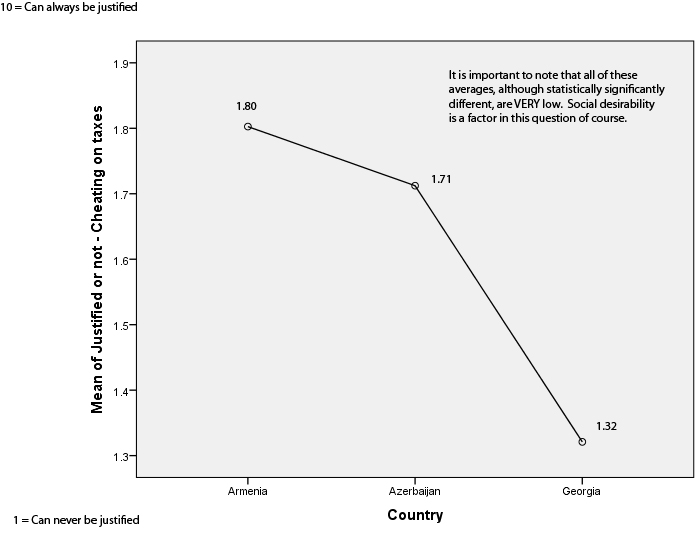

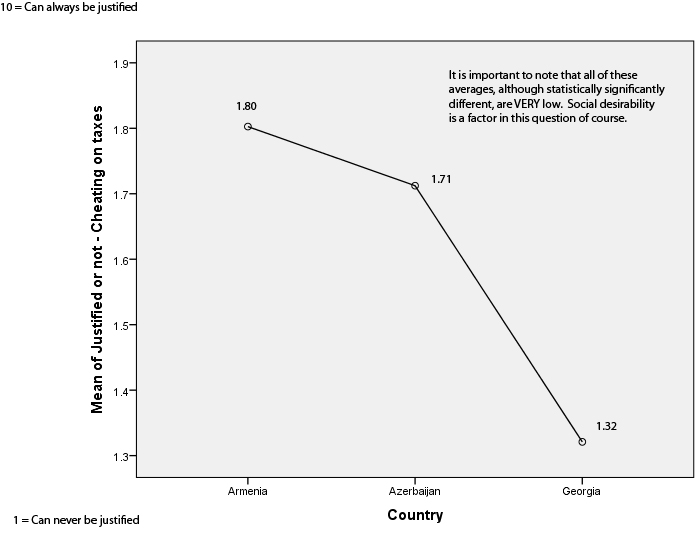

This is an analysis of the 2011 Caucasus Barometer. All differences are statistically significant. Although these questions were asked with a great deal of privacy, there is certainly a social desirability effect here.

People are asked if avoiding paying a fare on public transit was “ever justified” (scale 1 = can never be justified, 10 = can always be justified) and although this is a fairly low stakes behavior, people in the Caucasus were fairly (pun intended) against it.

And what about taxes? There are reported issues with people paying taxes at all levels. But again, people in the Caucasus were not keen on this.

“>

“>

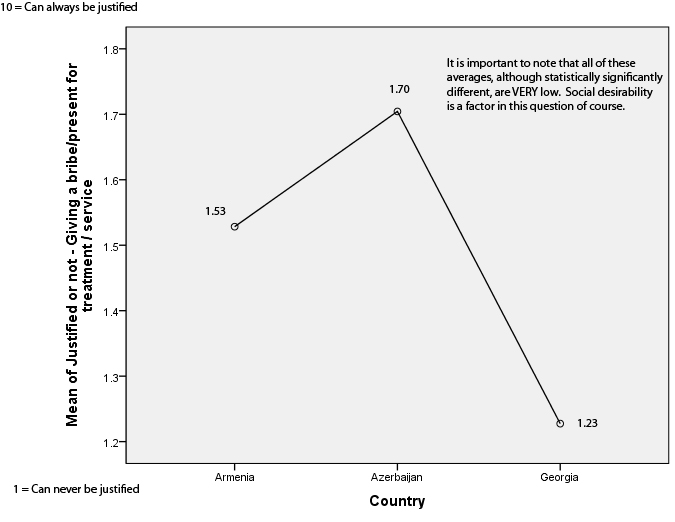

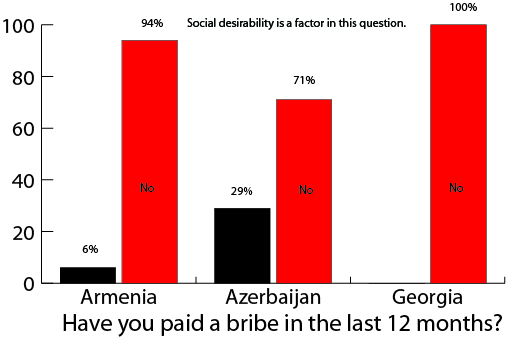

And everyone’s favorite – bribes!

No one in the Caucasus could justify accepting a bribe or present.

As far as giving bribes, few could justify it.

And when asked if they have given a bribe, NO GEORGIANS had given one! Wow. 6% of Armenians and 29% of Azerbaijanis though. This is interesting given the past two charts.

Overall, I’m not sure if justification of corruption has any implication on actual behaviors of corruption. It might not be justifiable to pay a bribe, but you do it anyway.

I think that it is telling that Georgians are the least tolerant of all of these types of low level corruption activities.

Social media in the Caucasus Part 2 — չորս քառակուսի, dörd kvadrat, ოთხი მოედანზე

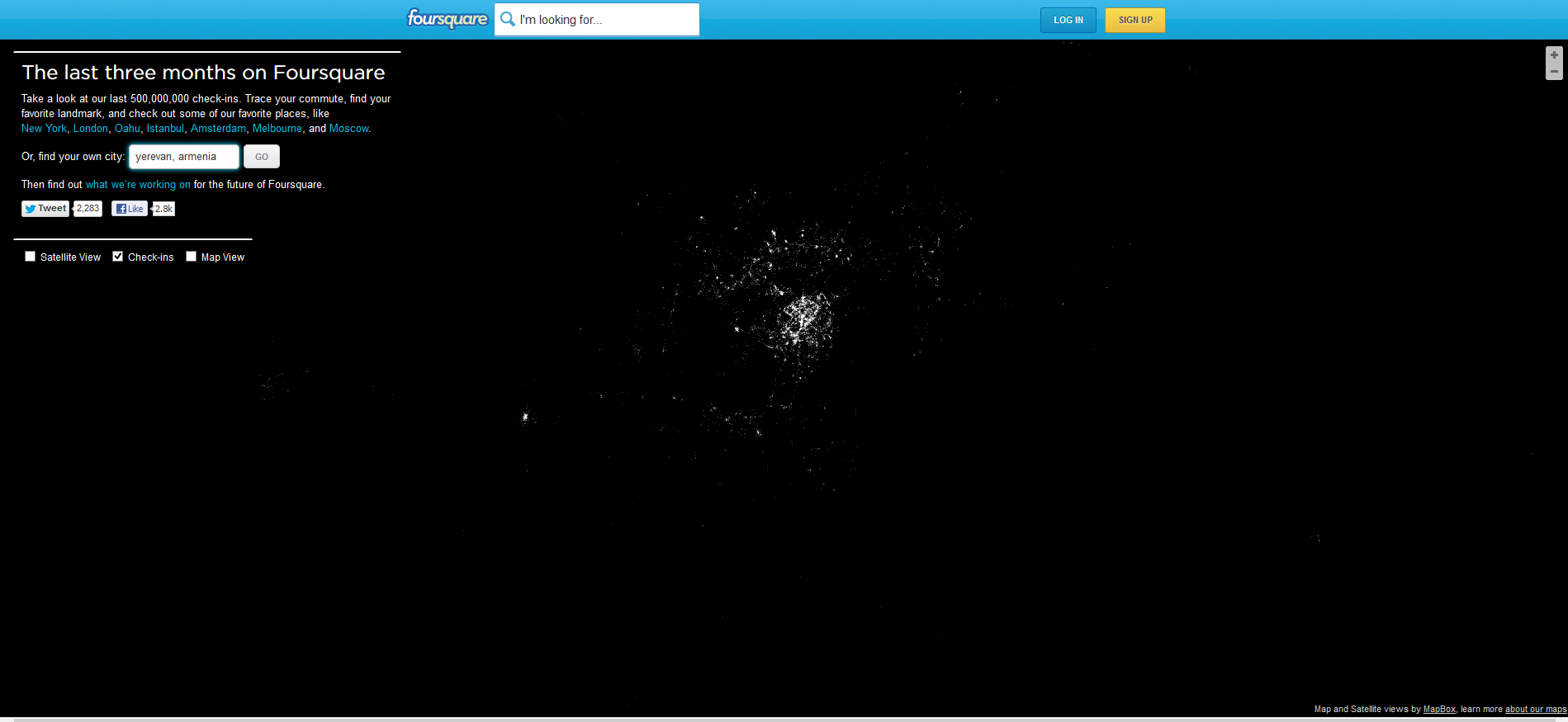

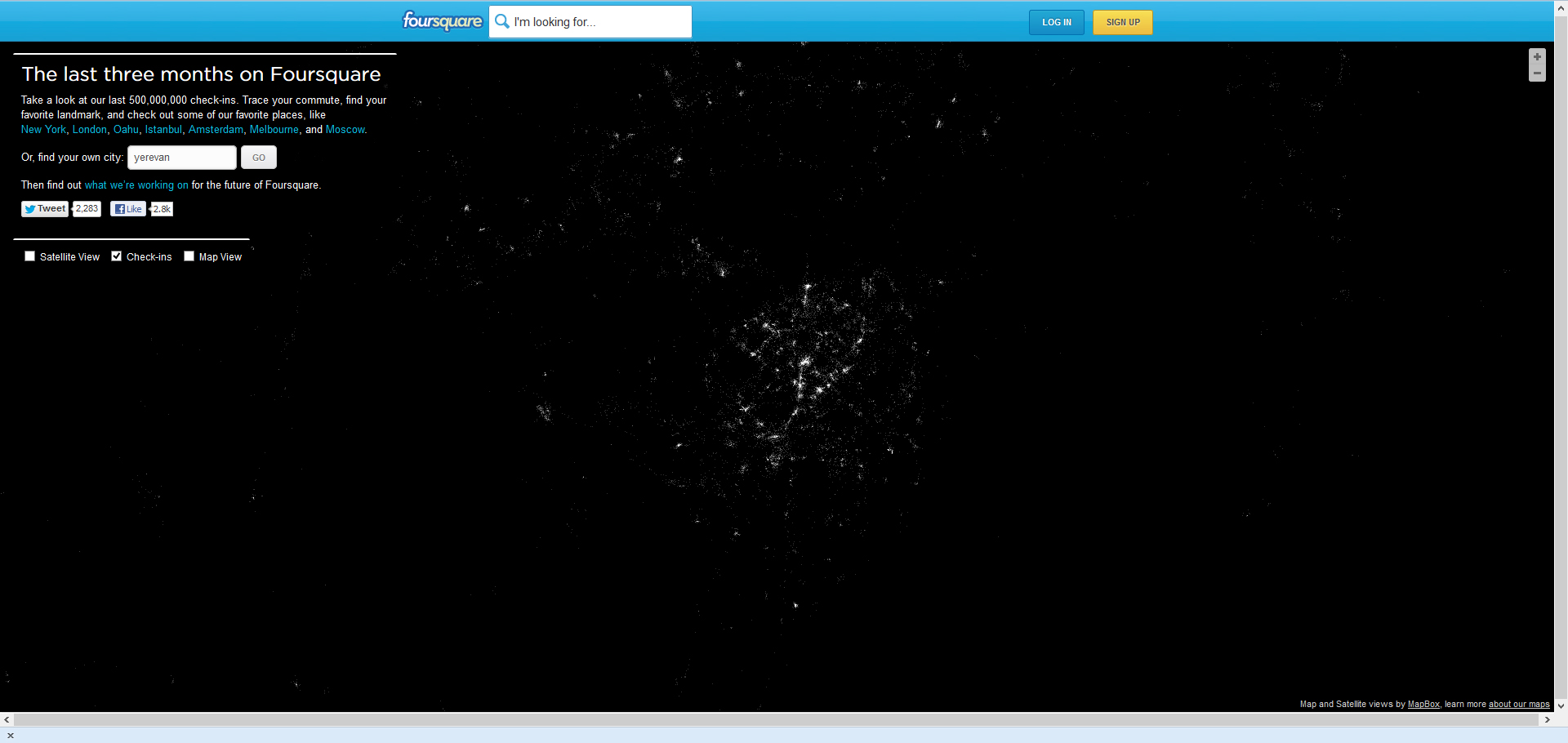

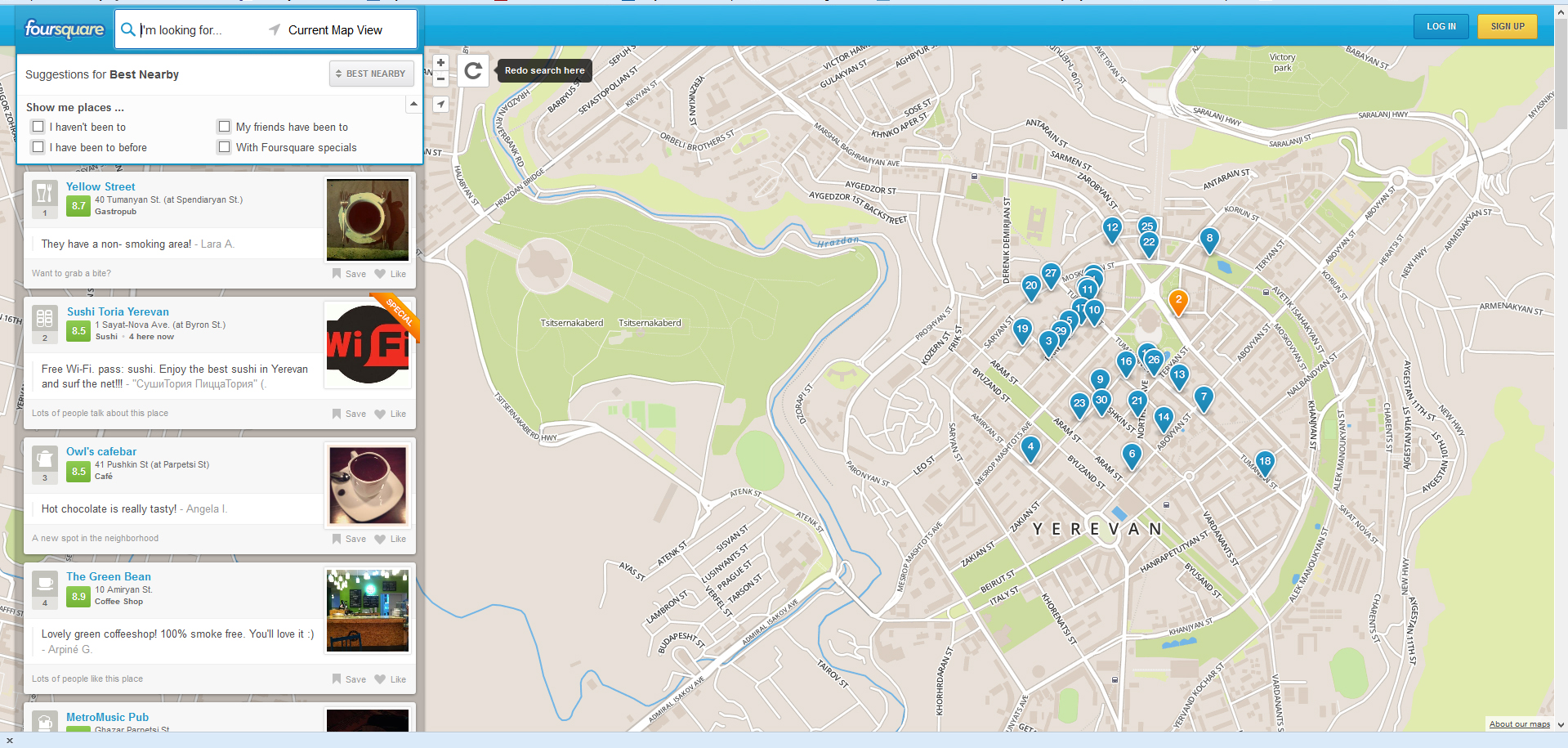

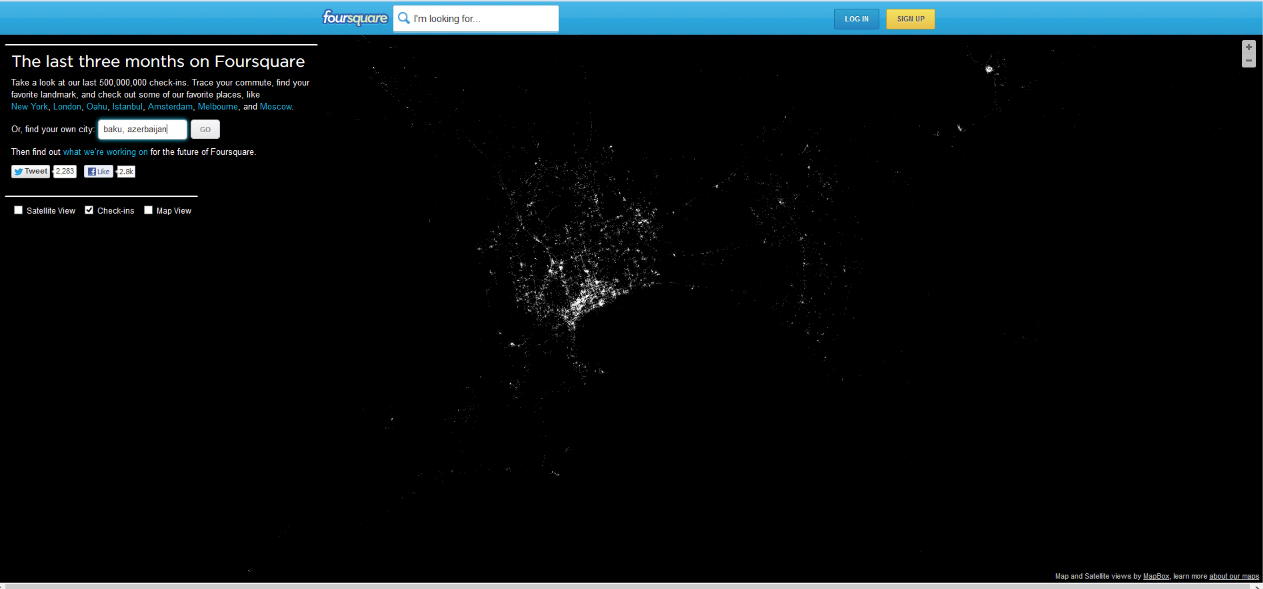

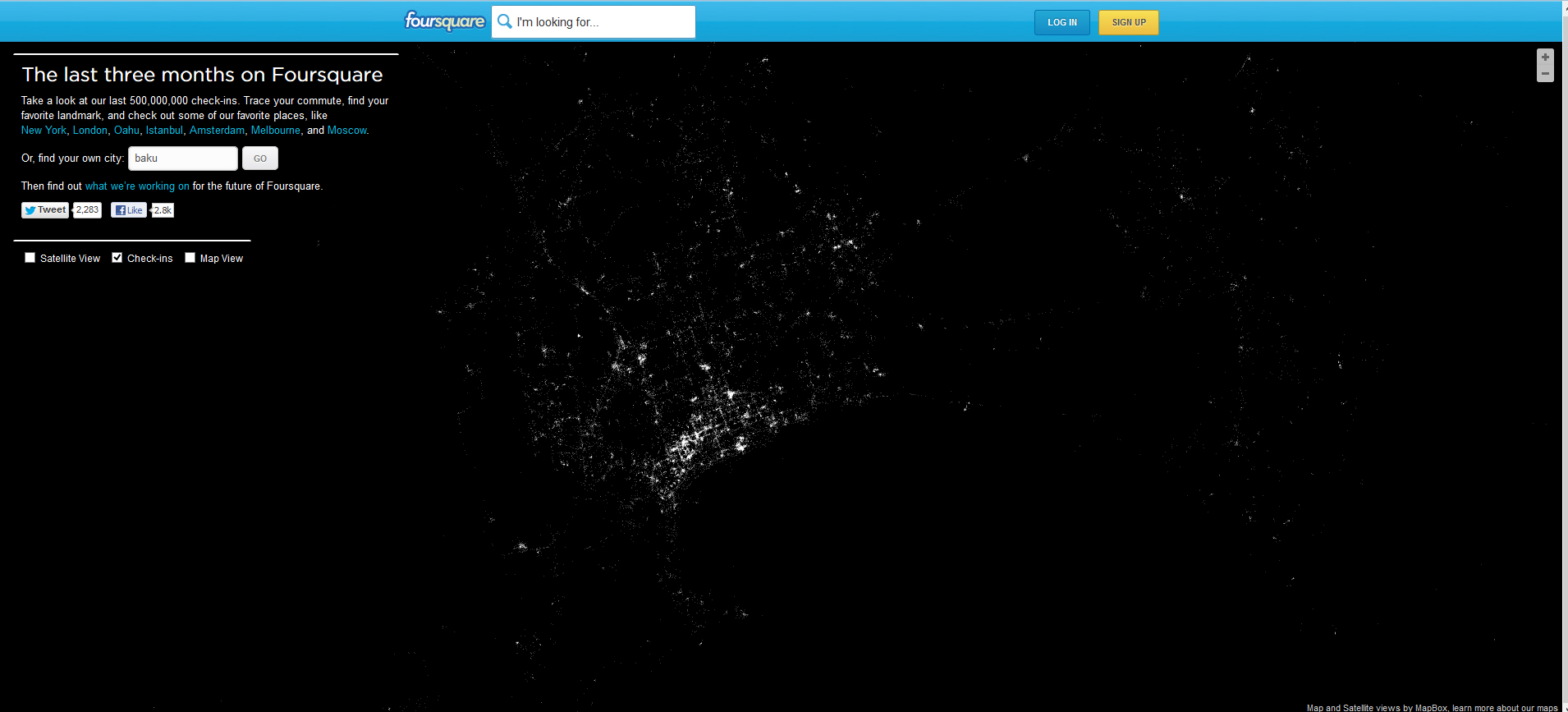

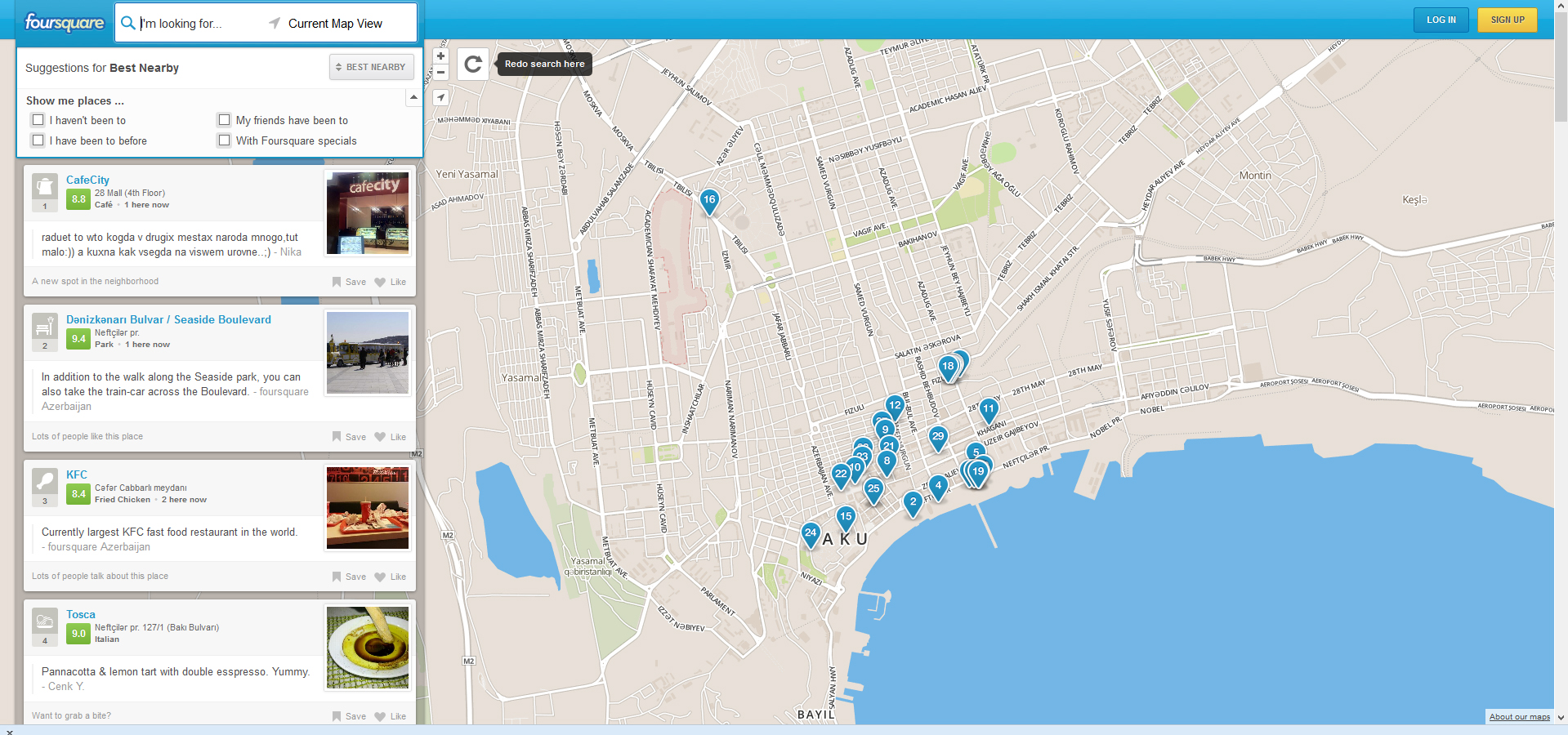

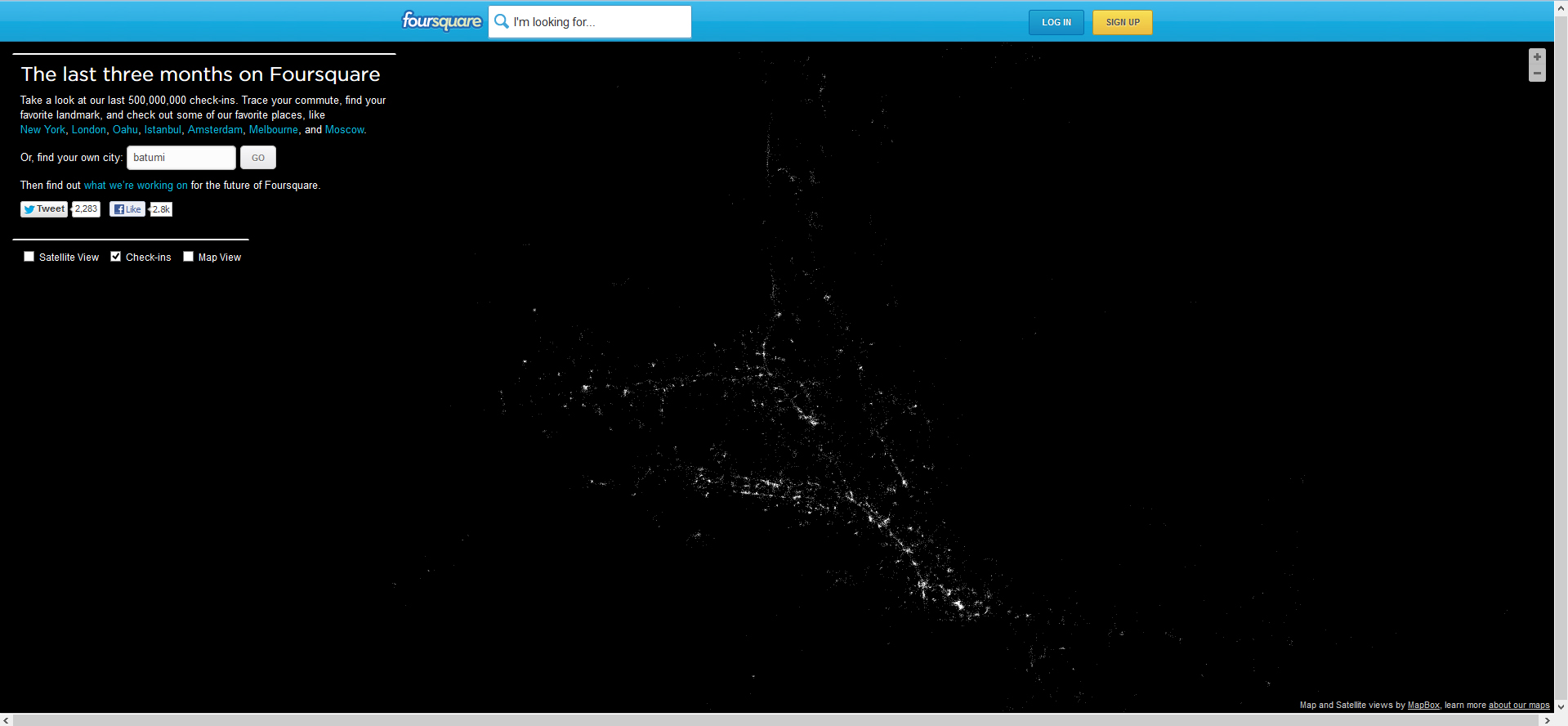

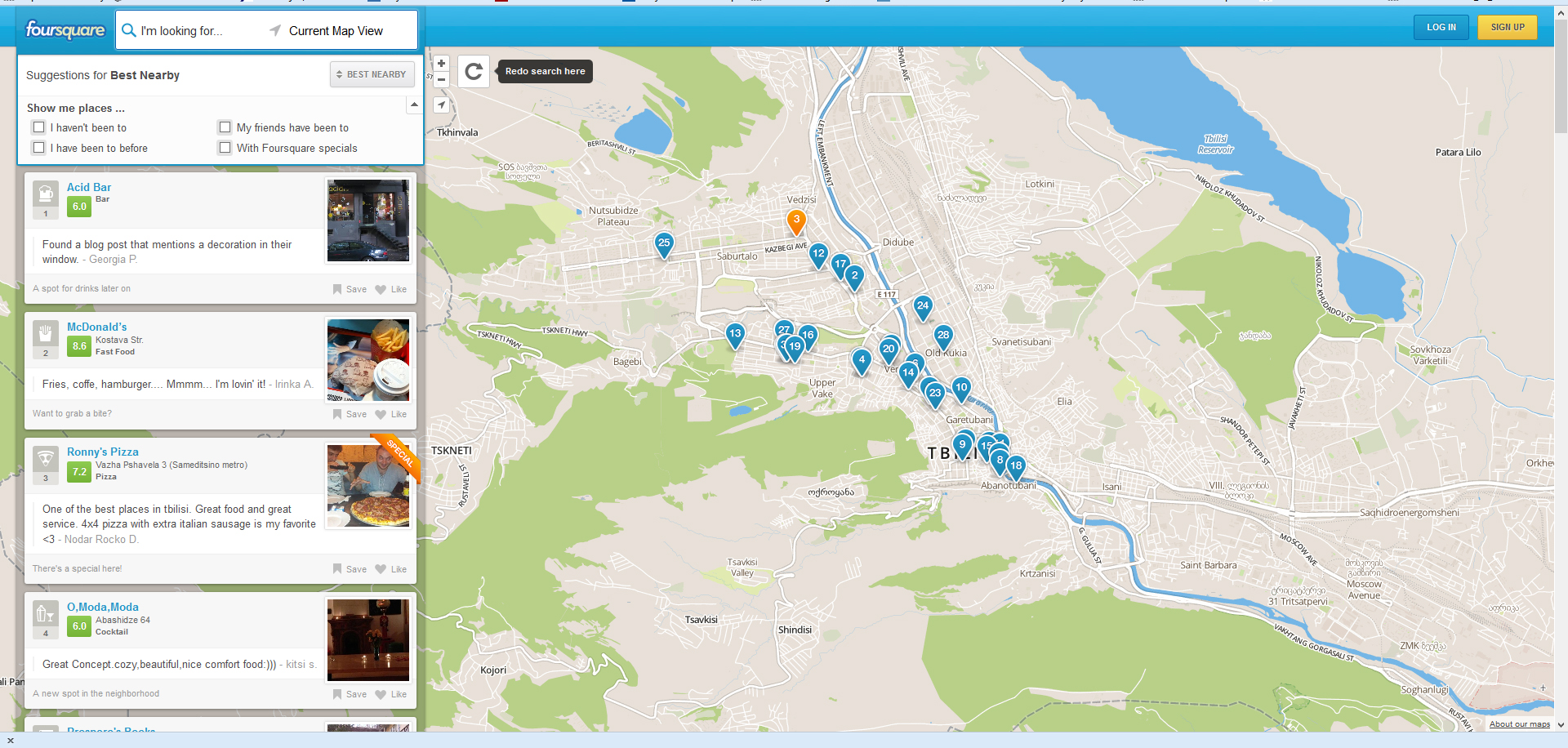

After yesterday’s post on my thoughts on social media in the Caucasus, I came across Foursquare maps of Yerevan, Baku, and Tbilisi. I love this sort of visualization and how you can sort of see the life of the city in it.

Foursquare is a mobile-based “game” (it gets its name from an American (?) children’s game where four kids bounce a large rubber ball between them in a square). One “checks in” at places. So, you’re at your kid’s school, you get on your phone and your GPS recognizes where you are and you “check in” to the school. Or you’re at a bar and you “check in.” If you’re the most frequent person that “checks in,” you become “mayor” of that place. Mayor is sort of meaningless, except when businesses give benefits to the mayor. The coffeeshop in my old neighborhood gave 50% off to the mayor!

Anyway, it is fairly popular amongst the geek scene in the Caucasus, so this is a little interesting.

Here’s Yerevan’s last three months of check-ins, as points of light

And close up

And the most popular check in spots in Yerevan (not sure if this is for all time or just recently)

Here’s Baku’s last three months of check-ins, as points of light

And close up

And the most popular check in spots in Baku (not sure if this is for all time or just recently)

Here’s Tbilisi’s last three months of check-ins, as points of light (I cannot figure out how Foursquare spells Tbilisi, so I went to Batumi and scrolled over)

And close up

And the most popular check in spots in Tbilisi (not sure if this is for all time or just recently)

Here is the link for looking at most popular and this is the light visualization page.

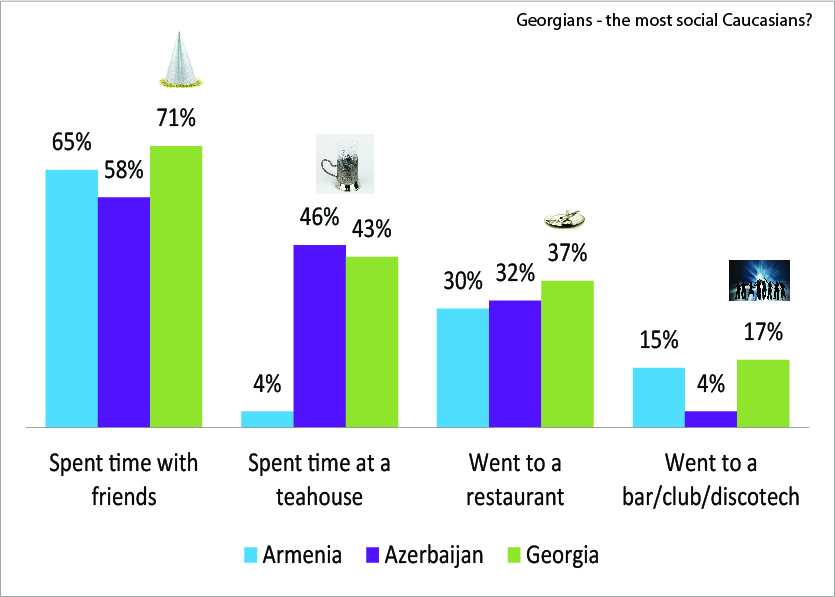

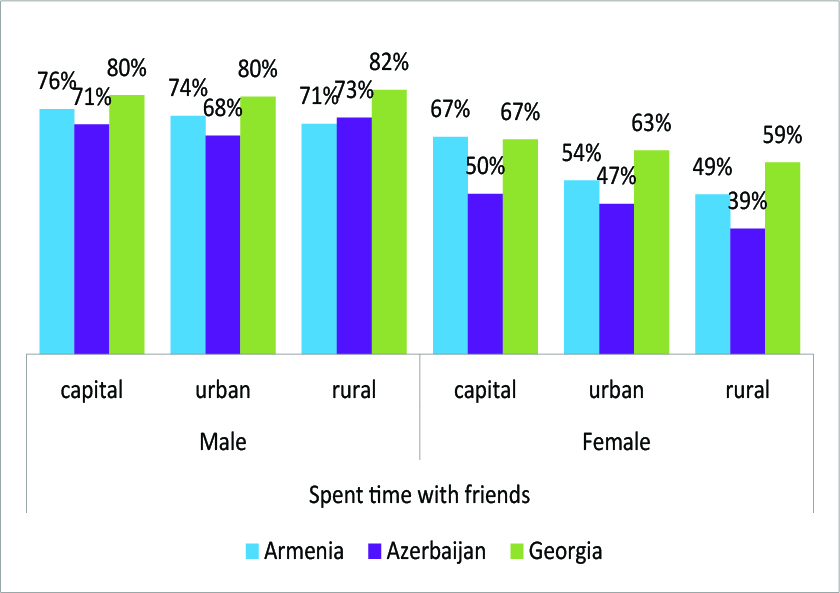

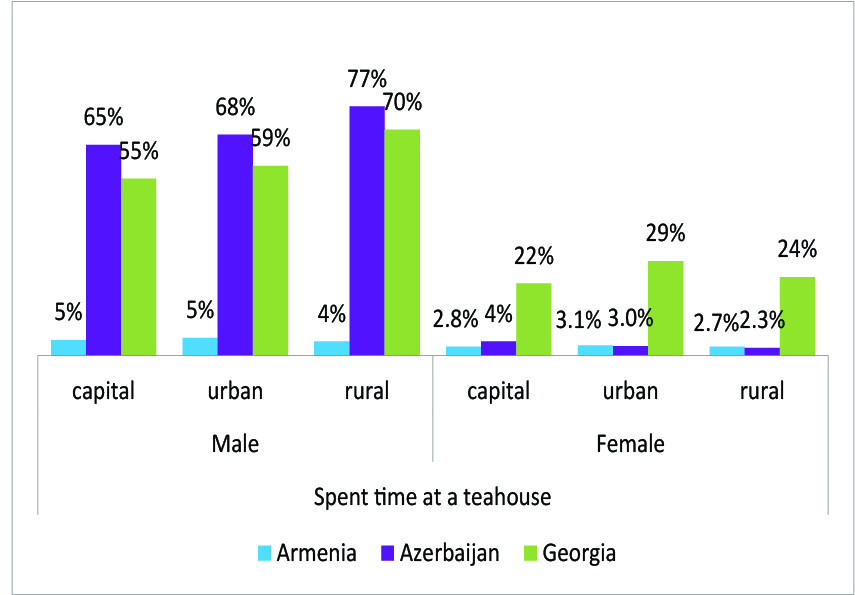

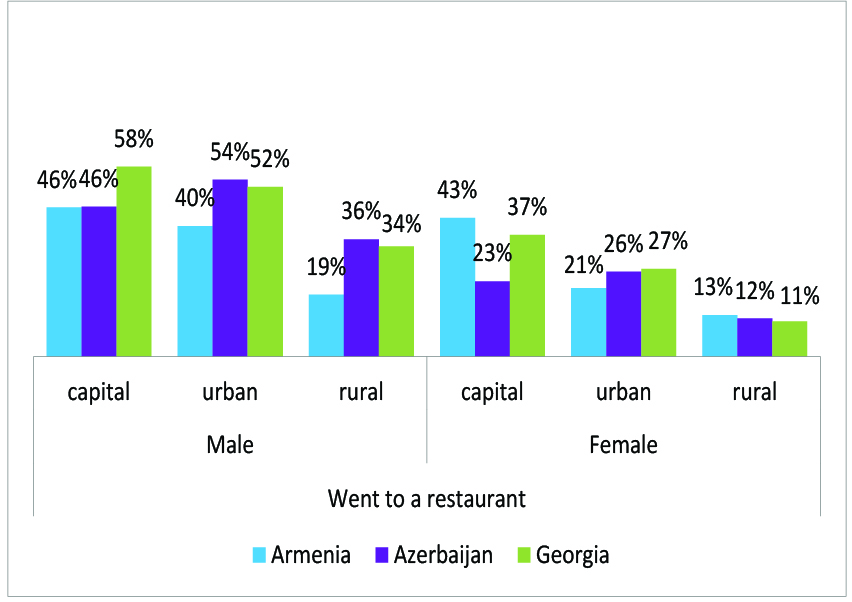

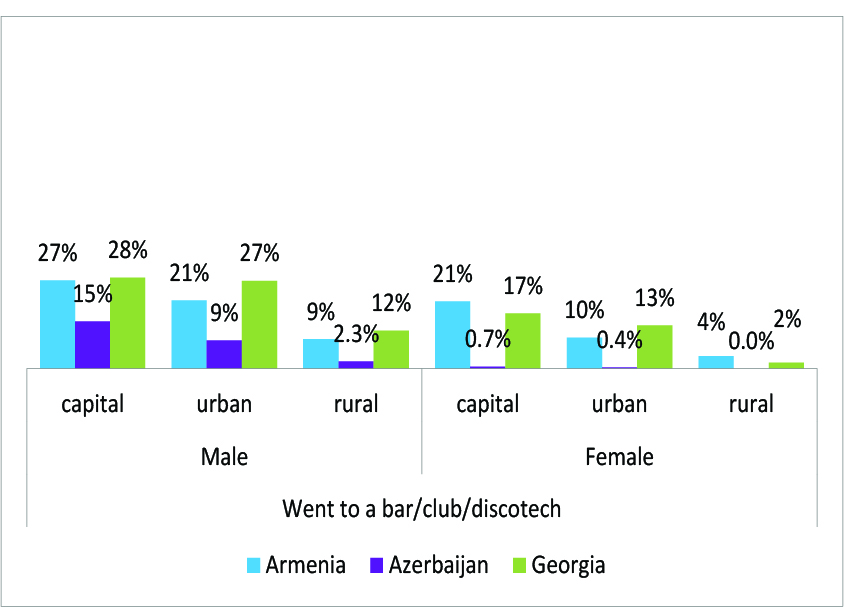

Georgians are social, women get out less than men do, and other unsurprising findings

2011 Caucasus Barometer

FWIW, Armenia doesn’t have a chaixana/birja culture.

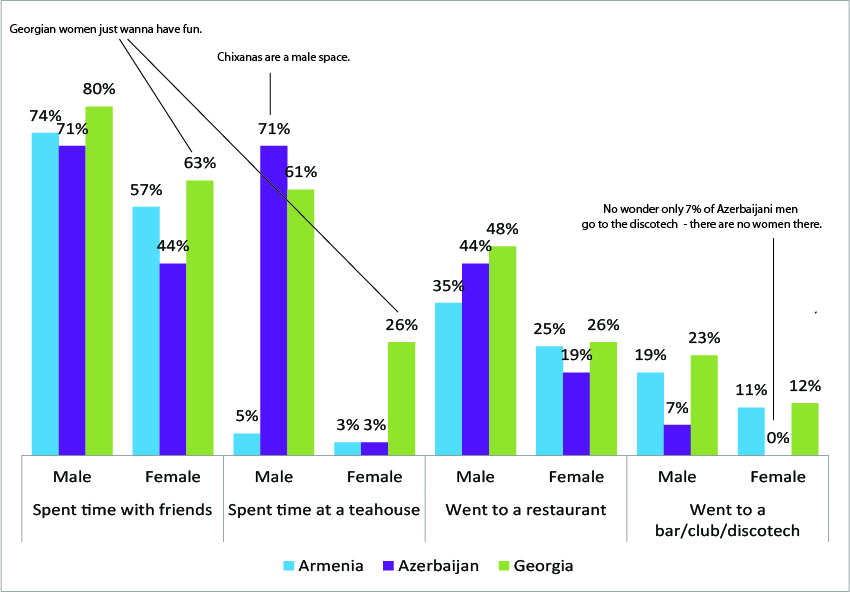

This was going to be the end of this blog post, but then I figured that I’d put a more interesting spin on it and look at gender as well. I noted some of the more interesting items, but please come to your own conclusions here.

ADDED LATER:

Ask and you shall receive! Here are breakdowns by region and gender and country for each of these activities. Certainly in the regions there are less opportunities to do some of these things because of availability (there is no discotech in my village!), lifestyle (I’m a farmer and need to get up early, so I can’t go to the discotech! or I’m a farmer and I’m too busy to hang out with friends during the harvesting season!), or cultural norms (maybe it isn’t okay for a village woman to do some of this stuff, while it would be more acceptable for a capital city woman).

This is a good example where women in regional cities and rural areas are just not going out to eat, with little difference between the three countries.

Here’s another interesting case – rural women in all three countries aren’t going out very often, although certainly in Azerbaijan it is less. But also note that few Azerbaijani rural men are going out either.

Tweet tweet – թռչուն, quş, ფრინველის, птица – social media in the Caucasus

With all of the Twitter analysis I’ve been doing lately, I’ve been seriously thinking about social media use in the Caucasus.

We know that a larger percentage of Georgians and Armenians are online than Azerbaijanis (2011 stats – I’ve seen the 2012 stats and this pattern continues) and weekly or more often adult Internet users are 30% of Armenians, 28% of Georgians, and 13% of Azerbaijanis (2011).

Armenia has 3,100,236 people, Azerbaijan 9,168,000 people, and Georgia 4,486,000 people – but that’s total population, we need to look at just adults (since that’s the data we have about Internet use – I fully acknowledge that teenagers are online and may be using social media). According to the World Bank, 20% of Armenians, 21% of Azerbaijanis, and 17% of Georgians are ages 0-14.

So, let’s take them out of the equation – (that’s 620,047 Armenians, 1,925,280 Azerbaijanis, and 762,620 Georgians) – and you have “adult” populations of 2,480,189 AM, 7,242,720 AZ, and 3,723,380 GE. So raw weekly or daily Internet users would be:

744,057 Armenia

941,554 Azerbaijan

1,042,546 Georgia

So in raw numbers, although the largest proportion of frequent Internet users exists in Armenia, Georgia has the largest sheer number of frequent Internet users.

In 2011, 6% of Armenians, 7% of Azerbaijanis, and 9% of Georgians (ADULTS) were on Facebook (let’s leave Odnoklassniki out of this for now). There is no Twitter data. I’ve seen 2012 and there is some growth, but not substantial. (And yes, I know socialbakers.com exists, but I really don’t trust it.)

Raw numbers then would be:

148,811 Armenia

506,990 Azerbaijan

335,104 Georgia

—

Okay, so back to my original point — I’ve noticed that the Azerbaijani Facebook and Twitter worlds is substantially more active than the Armenian one. (I acknowledge that I’m not up on what is going on in Georgia, but for reasons explained below, you’ll see that it is probably similar to Armenia). Why is this?

1. The raw numbers noted above — almost 5 times as many Azerbaijanis are on Facebook than Armenians. (I’m going to leave these countries’ diasporas out of this, but for what it’s worth, I feel like the Azerbaijani diaspora engages with Republic of Azerbaijan citizens more than Armenian diaspora do with Republic of Armenia citizens).

2. Because of the lack of free expression and assembly in Azerbaijan, most political discussion takes place on Facebook. Armenians can do this fairly freely in cafes or homes. Similarly, Armenians can organize and be political active in ways that Azerbaijanis cannot.

3. Language is a big part of this. As I wrote earlier this week, users of the Azerbaijani language are at a serious advantage over users of Armenian or Georgian because Azerbaijani uses the Latin script. This is also a special concern when it comes to Twitter and even more so when it comes to mobile phones (only the most recent Android OS has Armenian and Georgian, iPhone has it, but the others? No way). But my overall point is that there are barriers to Armenians and Georgians using these sites.

4. This is entirely speculative, but I get the sense that Bakuvians are just way more wired than Yerevantsis are. The Baku social media scene, beyond politics, is always jumpin’! There are a ton of Azerbaijani Instagrammers, Pinteresters, and other social media platform users. I just don’t see that same sort of scene in Yerevan. Yes, there is a bit of a FourSquare scene and of course people use these social media sites, but not to the extent that I see in Azerbaijan. (Although this may be a result of the sheer numbers!!)

I’m sure there are other reasons, and I’d love to hear comments…

Foreign language learning in the Caucasus

I am so impressed with the linguistic abilities of my Caucasus friends. Growing up in a culture where bilingualism is uncommon, I am so envious of all the languages spoken by these friends.

I have a piece in progress right now that looks at the influence of English language proficiency on Internet use in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Because of that I’ve been thinking about languages a lot.

Now, 2 decades after the Soviet Union collapsed, language attitudes are sort of all over the place. Here is some self-plagiarism (from the article mentioned above):

Language plays an important identity role in post-Soviet societies (Kleshik, 2010). In the Soviet period, the Caucasus were unique in that their national languages were considered official languages and government materials, media, and education were provided in both Russian and the local languages (Pavlenko, 2008). However, while Russian never became the dominant language in the Caucasus, high fluency in Russian was necessary for one to get ahead in the non-Russian Soviet republics. Urban families were able to choose to send their children to national or Russian language schools, and Russian schools generally were of better quality with newer textbooks. Traditionally the second language of choice would have been Russian (during the tsarist and Soviet periods); however, today, more and more young people are opting to learn English as well.

Armenian. Armenian is an Indo-European language with no strong relationship with other languages (Comrie, 1987) and a unique script dating to the fifth century. The script has not been well supported in computer operating systems, nor did a single encoding system dominate early computer use. It is very common, especially on mobile phones, for Armenian to be written in Latin script, developing into an informal orthography. Five to six million people speak Armenian (Grimes, 1992), although it is difficult to determine the number that can read and write, because for many speakers Armenian is a heritage language spoken in the household while the language of education and work is another language. Many families live in bi- or trilingual households and children are raised multilingual from birth (Petrossian, 1997).

Azerbaijani. Azerbaijani is closely related to Turkish. As Azerbaijani people lived under various empires, competing scripts (Perso-Arabic, Latin, Cyrillic) were used over different periods. In particular, during the Soviet period, Azerbaijanis in the Republic of Azerbaijan used Cyrillic, while Azerbaijanis in Iran used Perso-Arabic. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan decided to use the Turkish Latin script, although certainly older Azerbaijanis continue to use the script in which they were educated, Cyrillic. The move to the Turkish Latin alphabet benefits Azerbaijanis because there is no need for a special encoding script on personal computers or mobile phones (although ç becomes “c,” ı becomes “i”, ə because “e” or “a,” but in the context of a sentence, the replacement letter makes sense). There are likely about 20 million Azerbaijani speakers in the world. However, like Armenians, heritage speakers as well as the different scripts used mean that it is challenging for Azerbaijanis to communicate with each other via text.

Georgian. Georgian is a complex language that is part of the Kartvelian language family, unrelated to any other language. Like Armenian, Georgian has a unique script that has been a barrier for using technology, although writing Georgian in Latin script is not an uncommon workaround. Between 4-5 million people speak Georgian, but with some heritage speakers, it is unknown how many are literate.

Russian Language Skill. In the Soviet era, the Armenian language assumed a hegemonic function compared to many other republics because of a strong national intelligentsia (Suny, 1994). Russian remains the most popular second language and a great deal of Russian language media is present to this day. Between 74-87% of Armenians surveyed each year in 2006-2010 said that it is very important for Armenian children to learn Russian, and an additional 11-20% said that it is somewhat important (Gallup Organization, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010).

In Azerbaijan in the post-Soviet period, the government “demoted” Russian (banned in media and advertising in 2007) and promoted Turkish. Recently, English has become a popular second language choice as well (Shafiyeva & Kennedy, 2010). Nonetheless, Russian language instruction is still popular in Azerbaijan (Marquardt, 2011). Between 35-49% of Azerbaijanis surveyed each year in 2006-2010 said that it is very important for Azerbaijani children to learn Russian, and an additional 39-50% said that it is somewhat important (Gallup Organization, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010).

In Georgia during the Soviet era, the Georgian language remained a strong part of public life, although Russian was still considered an elite language. In 1970, most rural Georgians (91.4%) and over half of urban Georgians (63%) had low proficiency in Russian (Suny, 1994). In the post-Soviet period, because of Georgia’s poor relationship with Russia, the Russian language has been strongly discouraged at the governmental level (banned in advertising and media in 2004), although citizens still believe that it is a useful language to know (Kleshik, 2010). Between 43-69% of Georgians surveyed each year in 2006-2010 said that it is very important for Georgian children to learn Russian, and an additional 27-40% said that it is somewhat important (Gallup Organization, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010).

English. Based on the author’s observations, English language learning seems to have become more popular in these countries since the 1990s. At least in Azerbaijan, others confirm that English has become a popular second language choice (Shafiyeva & Kennedy, 2010). But English language education is not available to all. Urbanites and the rich have greater access to schools with English language instruction as well as private tutoring that would allow someone to reach a higher level of proficiency (Pearce, 2011).

—-

So, with that, I wanted to look at attitudes toward foreign language instruction. In the 2011 Caucasus Barometer, people were asked if any foreign language should be mandatory in school (none, any, Russian, English, and other were the choices — I wish this had been open ended, but whatever… The lack of Turkish as a choice for Azerbaijan bothers me the most).

Let’s be honest – Armenian and Georgian especially are not the most practical languages to know, in terms of global opportunities. Because of this, I speculated that more upwardly mobile people would be more keen on foreign language instruction.

These graphics were created by Katy Pearce based on her analysis of the 2011 Caucasus Barometer. Any questions should be directed to @katypearce on Twitter.

This is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. Based on a work at www.katypearce.net. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://www.katypearce.net/cv/info.