Tweet tweet – թռչուն, quş, ფრინველის, птица – social media in the Caucasus

With all of the Twitter analysis I’ve been doing lately, I’ve been seriously thinking about social media use in the Caucasus.

We know that a larger percentage of Georgians and Armenians are online than Azerbaijanis (2011 stats – I’ve seen the 2012 stats and this pattern continues) and weekly or more often adult Internet users are 30% of Armenians, 28% of Georgians, and 13% of Azerbaijanis (2011).

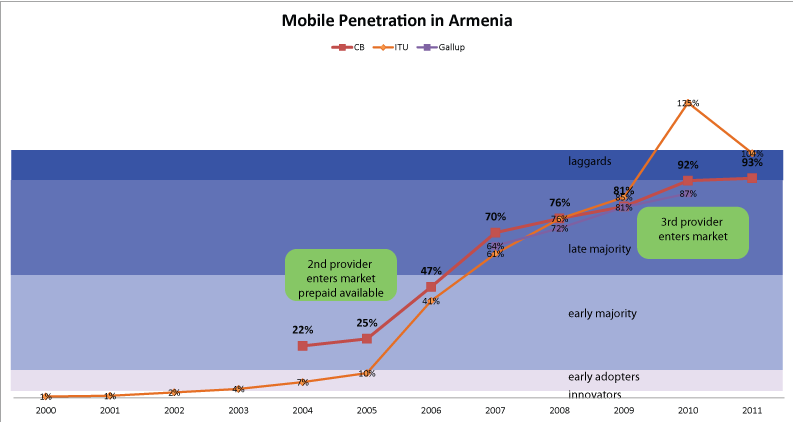

Armenia has 3,100,236 people, Azerbaijan 9,168,000 people, and Georgia 4,486,000 people – but that’s total population, we need to look at just adults (since that’s the data we have about Internet use – I fully acknowledge that teenagers are online and may be using social media). According to the World Bank, 20% of Armenians, 21% of Azerbaijanis, and 17% of Georgians are ages 0-14.

So, let’s take them out of the equation – (that’s 620,047 Armenians, 1,925,280 Azerbaijanis, and 762,620 Georgians) – and you have “adult” populations of 2,480,189 AM, 7,242,720 AZ, and 3,723,380 GE. So raw weekly or daily Internet users would be:

744,057 Armenia

941,554 Azerbaijan

1,042,546 Georgia

So in raw numbers, although the largest proportion of frequent Internet users exists in Armenia, Georgia has the largest sheer number of frequent Internet users.

In 2011, 6% of Armenians, 7% of Azerbaijanis, and 9% of Georgians (ADULTS) were on Facebook (let’s leave Odnoklassniki out of this for now). There is no Twitter data. I’ve seen 2012 and there is some growth, but not substantial. (And yes, I know socialbakers.com exists, but I really don’t trust it.)

Raw numbers then would be:

148,811 Armenia

506,990 Azerbaijan

335,104 Georgia

—

Okay, so back to my original point — I’ve noticed that the Azerbaijani Facebook and Twitter worlds is substantially more active than the Armenian one. (I acknowledge that I’m not up on what is going on in Georgia, but for reasons explained below, you’ll see that it is probably similar to Armenia). Why is this?

1. The raw numbers noted above — almost 5 times as many Azerbaijanis are on Facebook than Armenians. (I’m going to leave these countries’ diasporas out of this, but for what it’s worth, I feel like the Azerbaijani diaspora engages with Republic of Azerbaijan citizens more than Armenian diaspora do with Republic of Armenia citizens).

2. Because of the lack of free expression and assembly in Azerbaijan, most political discussion takes place on Facebook. Armenians can do this fairly freely in cafes or homes. Similarly, Armenians can organize and be political active in ways that Azerbaijanis cannot.

3. Language is a big part of this. As I wrote earlier this week, users of the Azerbaijani language are at a serious advantage over users of Armenian or Georgian because Azerbaijani uses the Latin script. This is also a special concern when it comes to Twitter and even more so when it comes to mobile phones (only the most recent Android OS has Armenian and Georgian, iPhone has it, but the others? No way). But my overall point is that there are barriers to Armenians and Georgians using these sites.

4. This is entirely speculative, but I get the sense that Bakuvians are just way more wired than Yerevantsis are. The Baku social media scene, beyond politics, is always jumpin’! There are a ton of Azerbaijani Instagrammers, Pinteresters, and other social media platform users. I just don’t see that same sort of scene in Yerevan. Yes, there is a bit of a FourSquare scene and of course people use these social media sites, but not to the extent that I see in Azerbaijan. (Although this may be a result of the sheer numbers!!)

I’m sure there are other reasons, and I’d love to hear comments…