Interpersonal trust is, arguably, the most important concept for a society. Interpersonal trust is understood as the general inclination of people to trust their fellow citizens (Hall, 2002). Interpersonal trust is related to EVERYTHING – democratization, economic wellbeing… you name it.

I did an analysis of some of the trust measures in the ERBD Life in Transition survey from 2011.

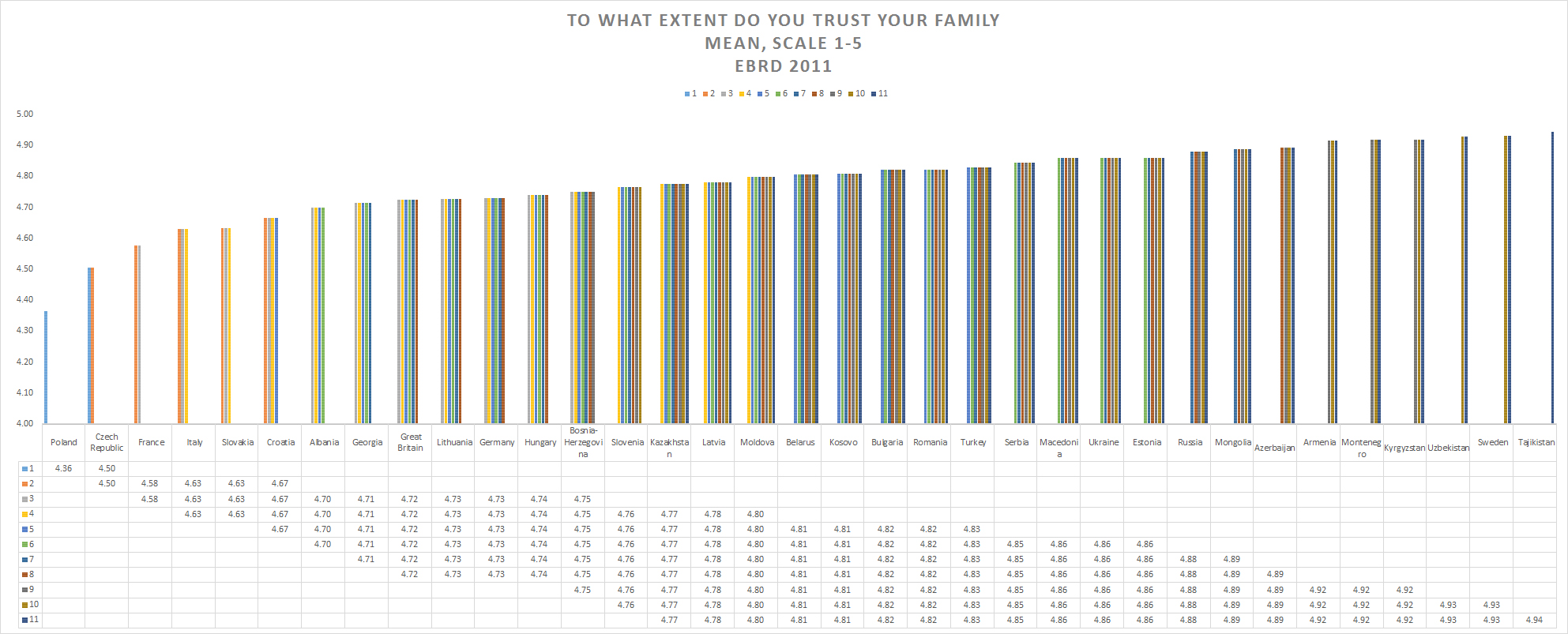

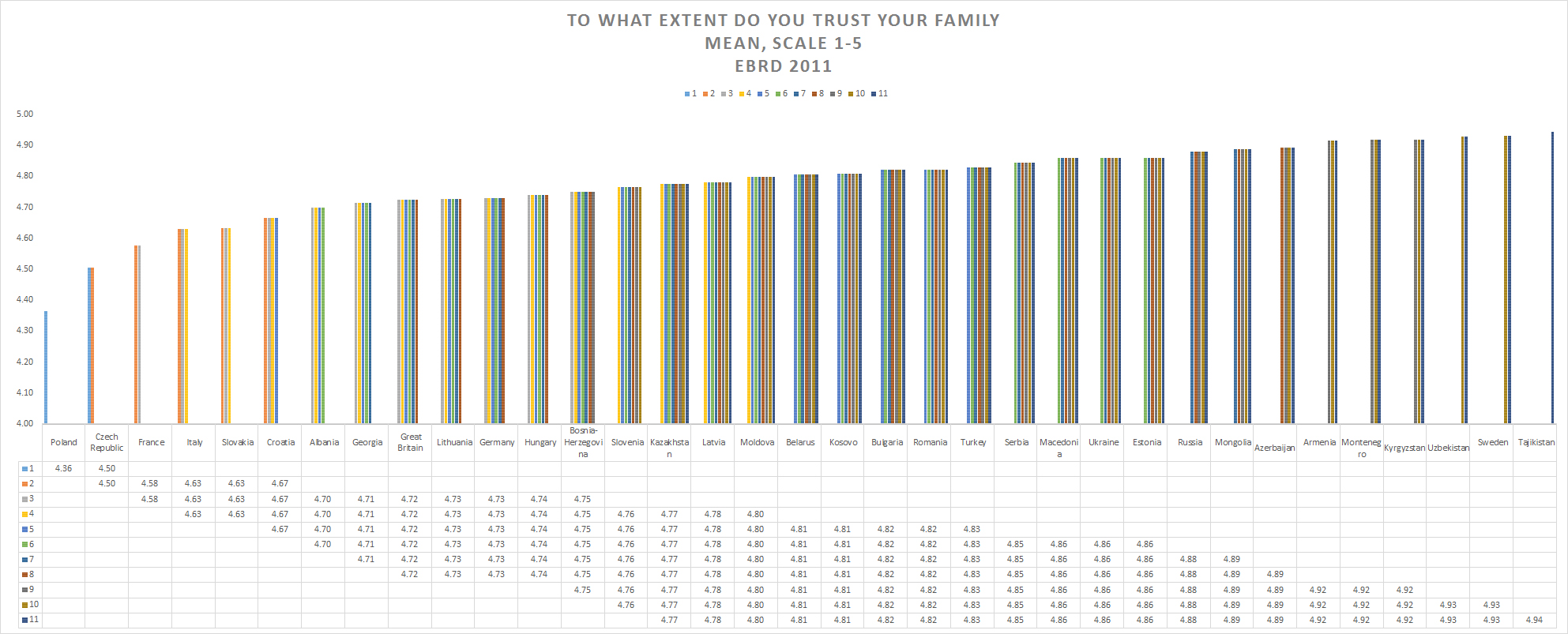

The first question asks to what extent people trust their family. So since it was a scale of 1-5 (1 = completely distrust; 5 = completely trust), you can see that people in nearly every country trust their families!

These groupings 1-11 are statistically significant differences in the averages. Countries are listed in multiple columns because, for example, there is no statistically significant difference between Poland and the Czech Republic. But there is also no difference between the Czech Republic and France. Yet there is a difference between Poland and France. Make sense?

Poles are the least trustful of their family (but again, a 4.36/5 – still really trusting!) and Tajiks are the most trusting. There is an argument that poverty results in higher trust because you need these people to survive. Yet, Sweden (as usual) is at the height of family trust. Of interest to this blog’s readers, Armenians and Azerbaijanis really trust their families 4.92 and 4.89/5. Georgians are a little lower at 4.71/5.

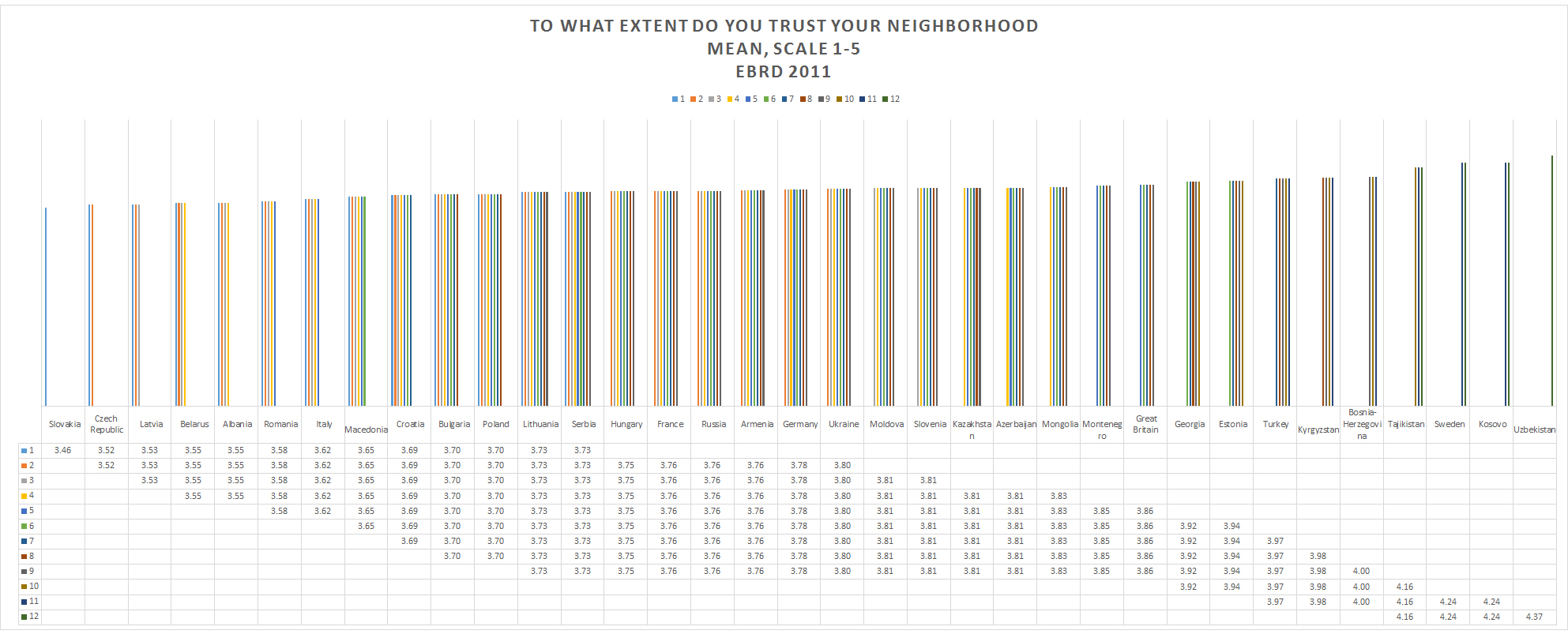

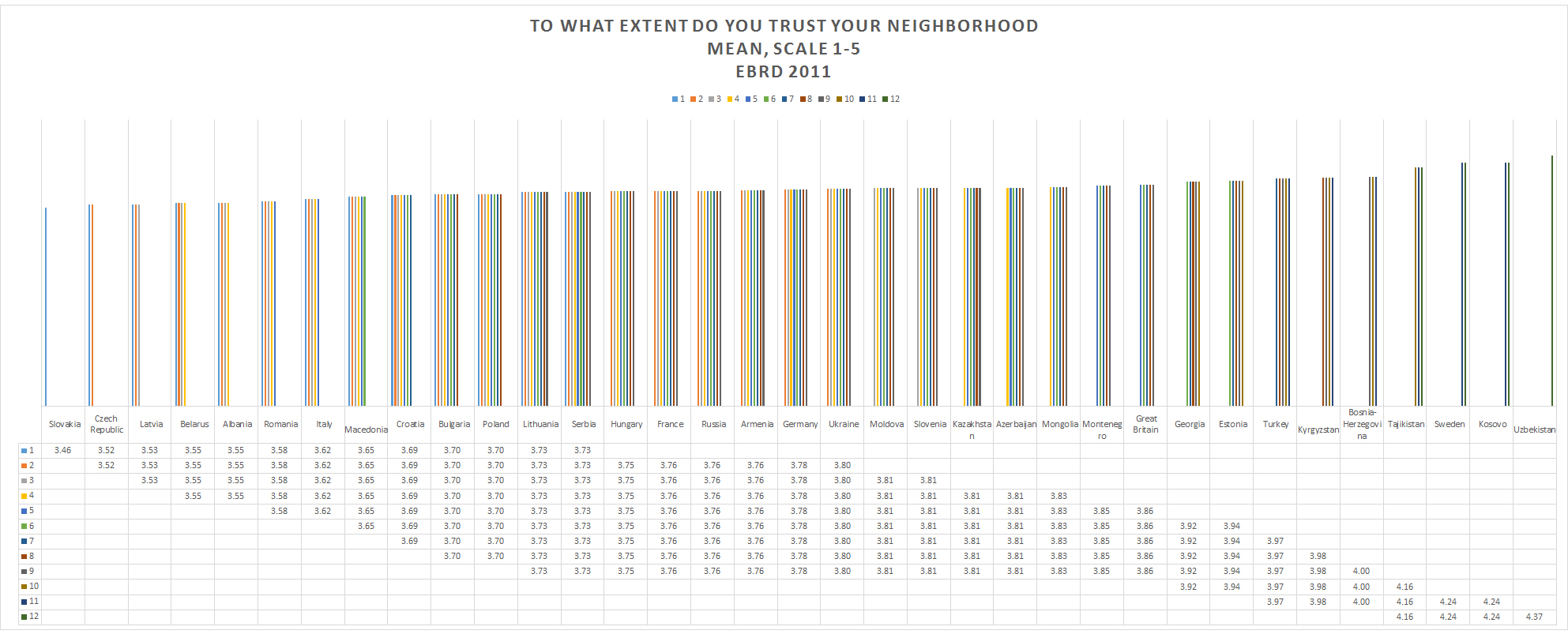

The next question asks about trusting one’s neighbors. I suspect that there are some rural/urban differences here, but for the purpose of this blog post, I’m focusing on country-level.

Slovakians are the least trusting with 3.46/5. Uzbeks are the highest with 4.37/5 (although, as I’ve written before, I don’t really trust the Uzbek data in this study.) Georgians are fairly trusting of neighbors with 3.92/5; Azerbaijanis at 3.81/5; and Armenians at 3.76/5.

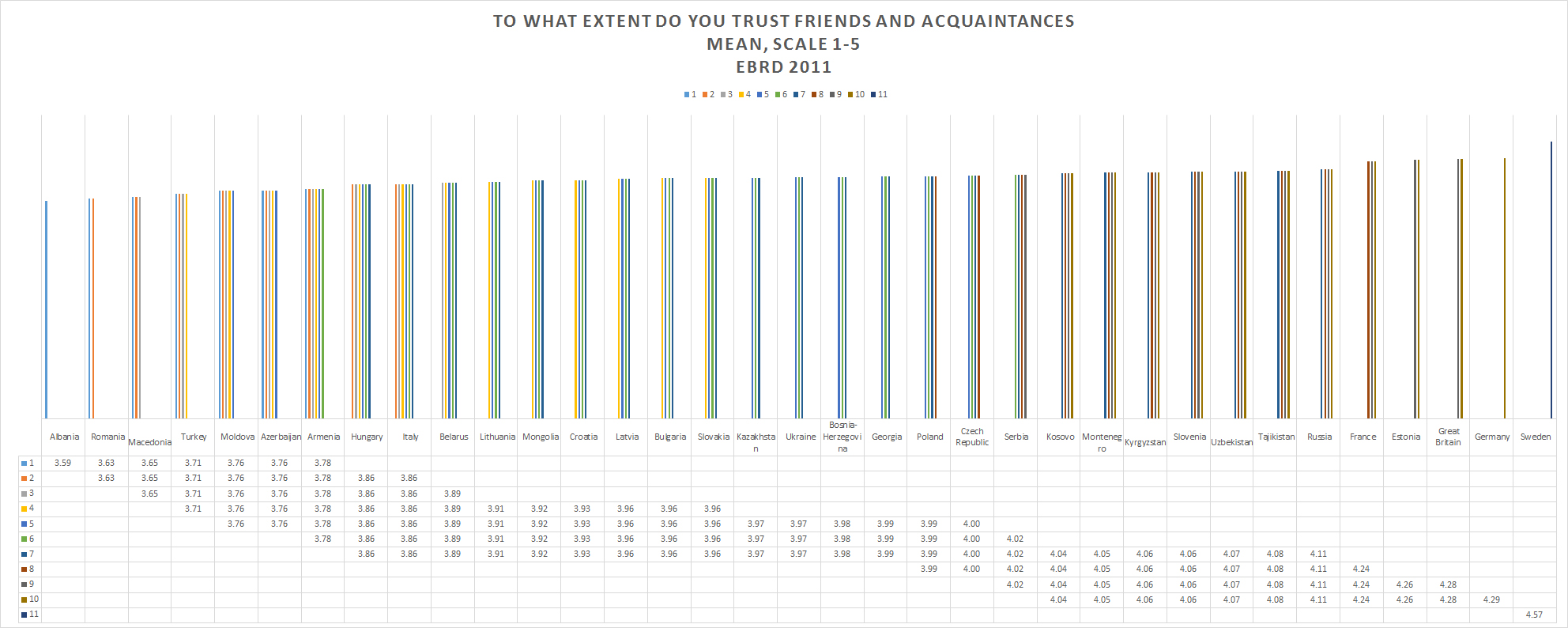

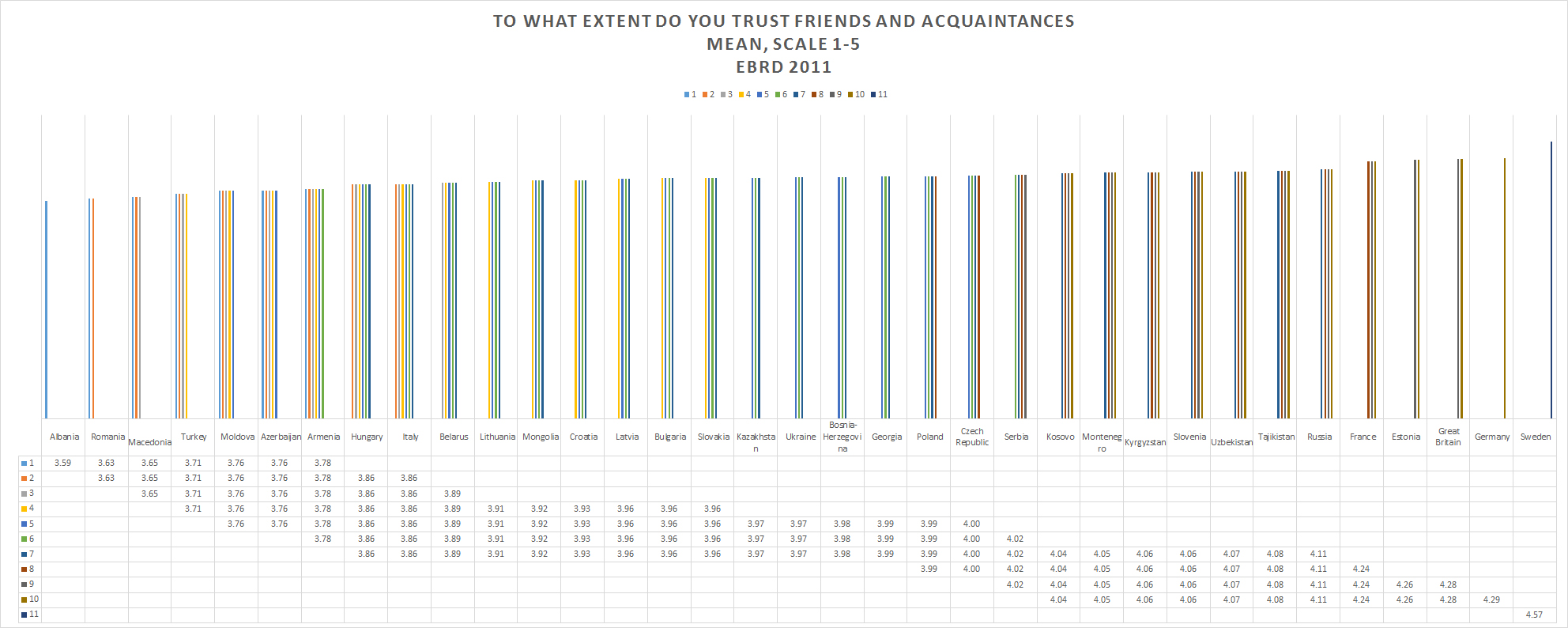

Then trusting one’s friends, where Albanians are the least trusting with 3.59/5. Azerbaijanis and Armenians aren’t terribly trusting of their friends either – 3.76 and 3.78/5. Again, Swedes are the most trusting of friends with 4.57/5.

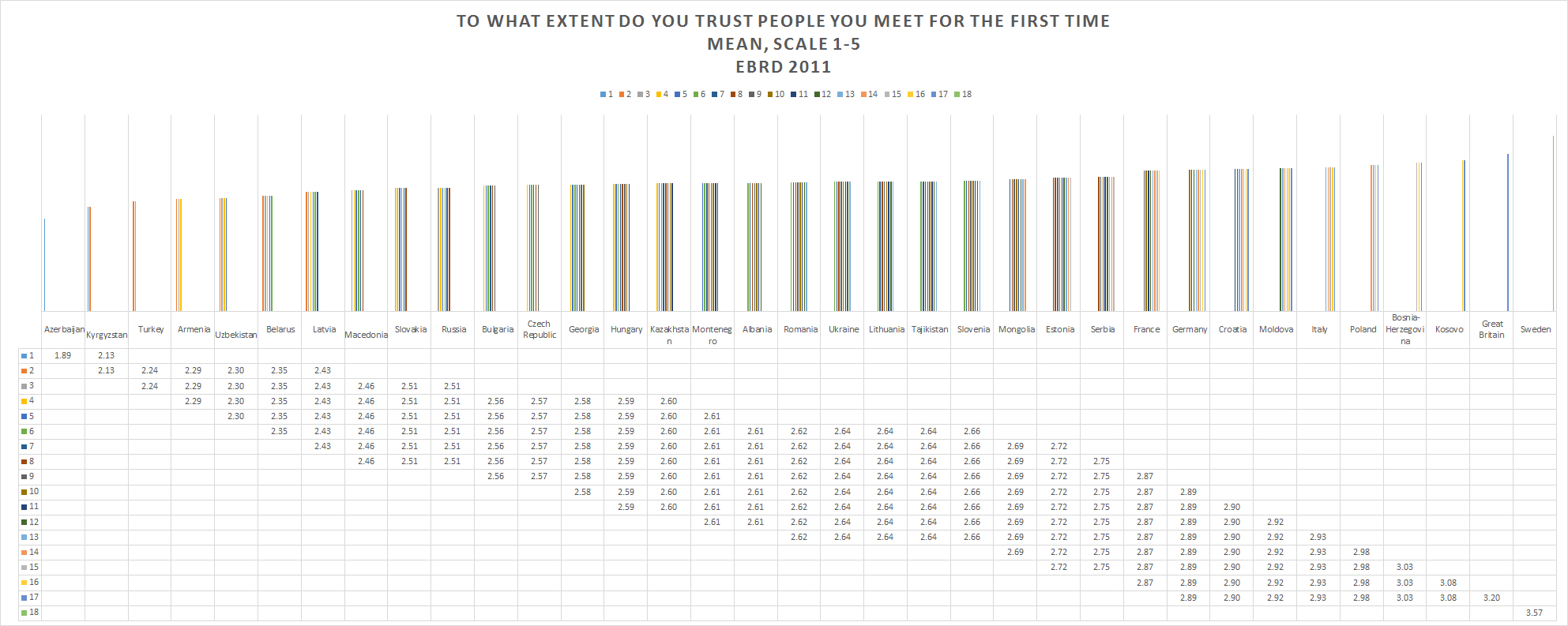

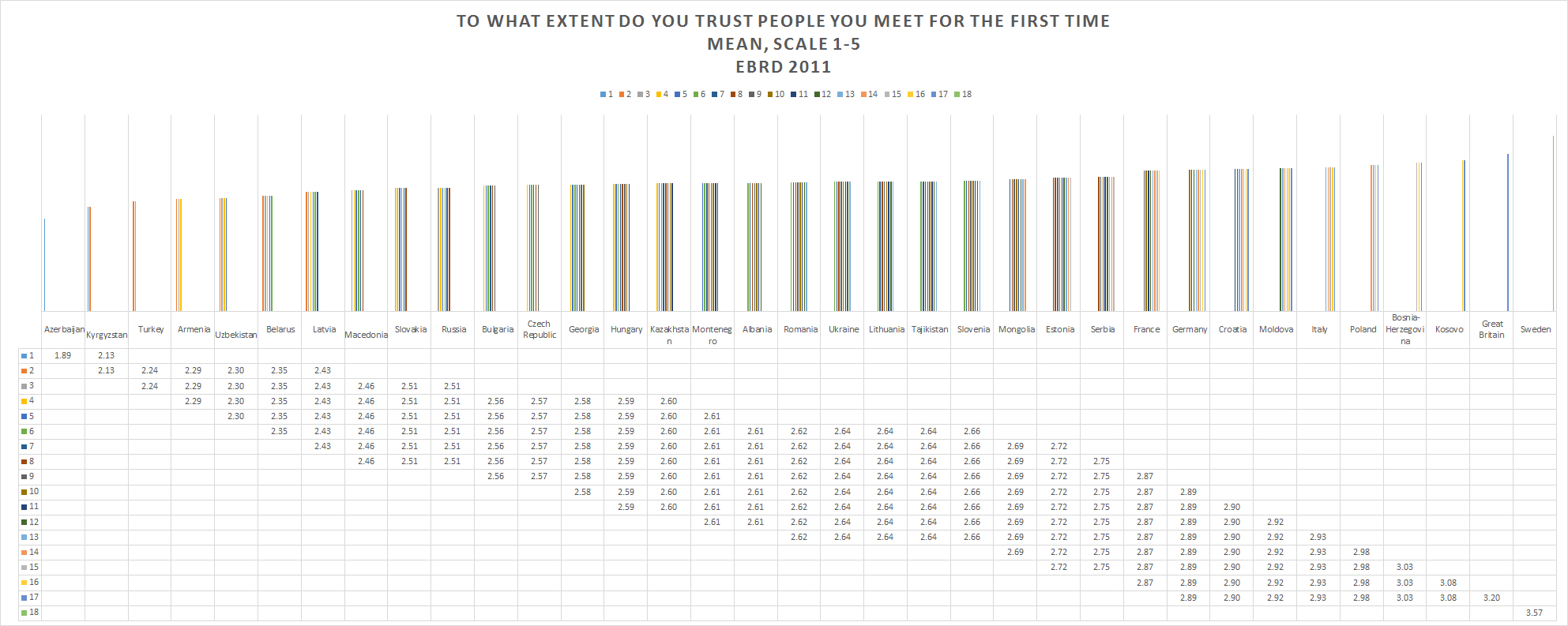

Next is people you meet for the first time. This is really important.

Azerbaijanis are the lowest with 1.89/5! Wow – Azerbaijanis REALLY don’t trust new people, do they? Wow! Armenians aren’t too trusting either, 2.29/5, but still, significantly higher than Azerbaijanis. Swedes are the most trusting, 3.57/5. Georgians fall in the middle, 2.58/5.

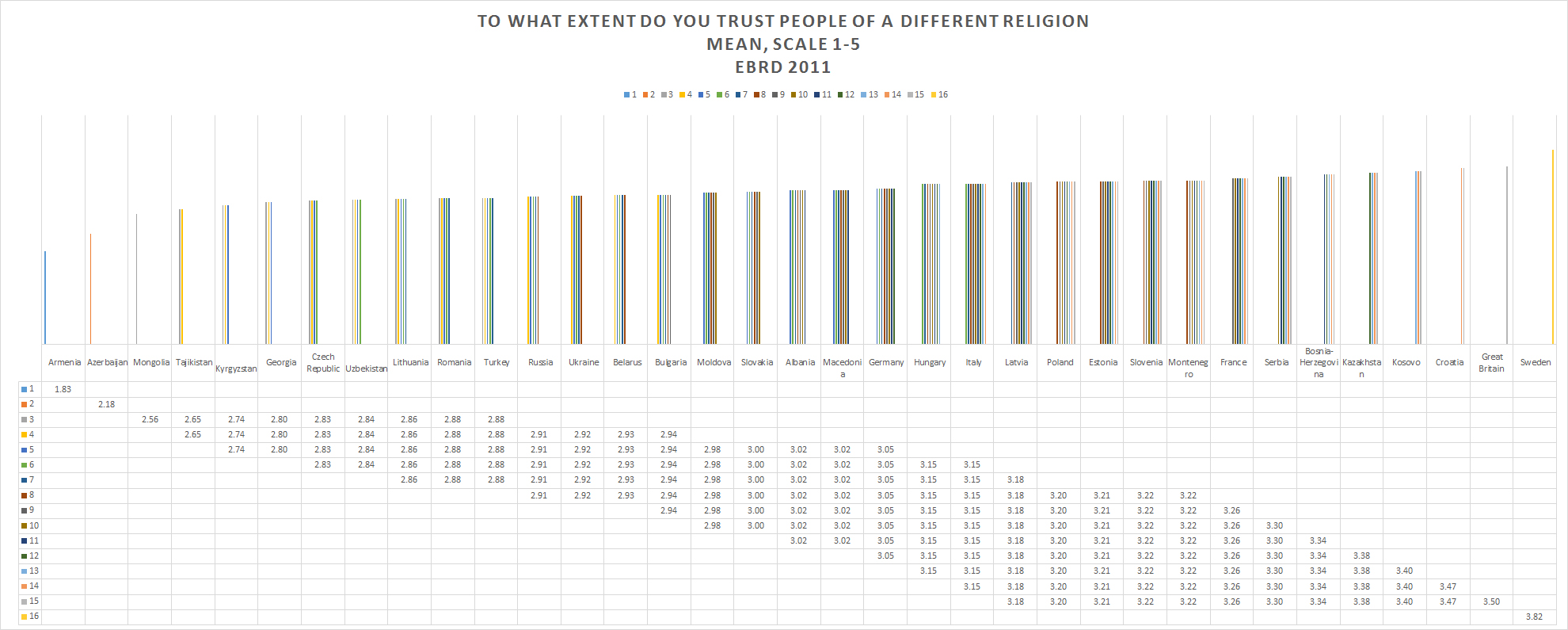

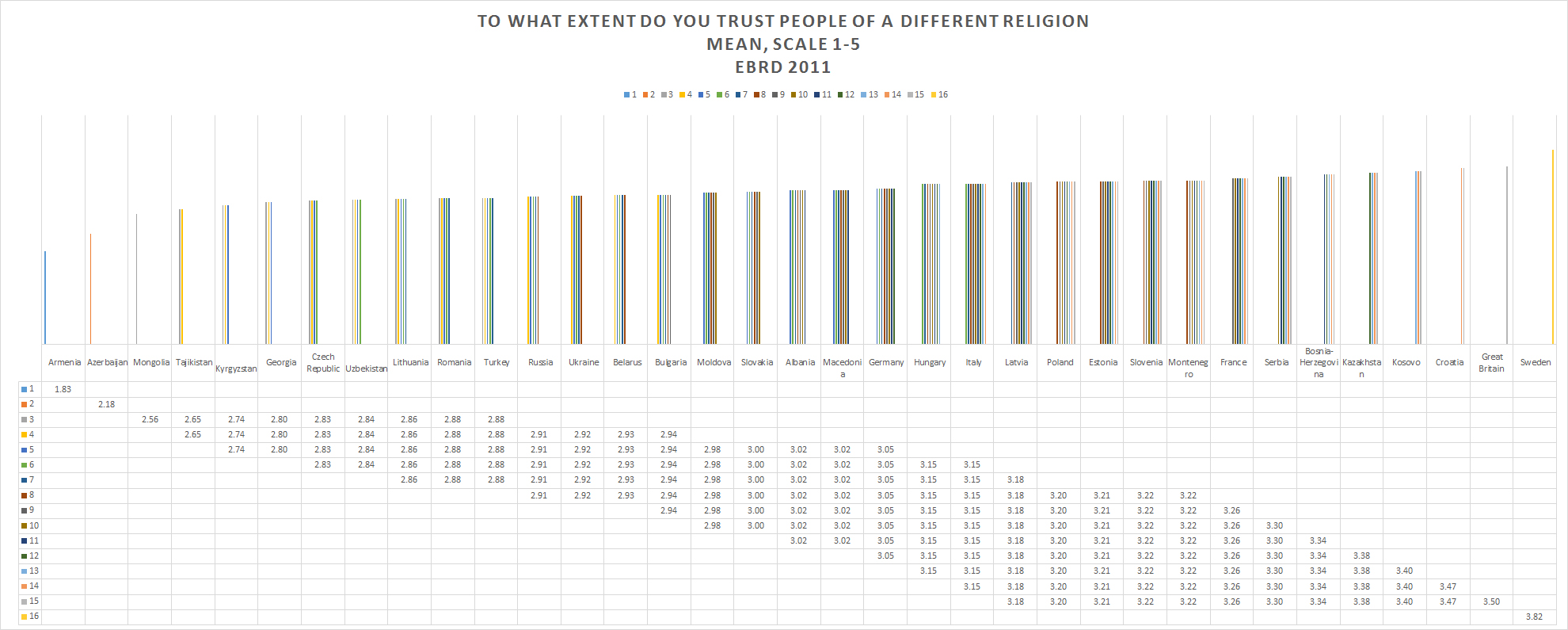

People of another religion is next. Armenia, a very homogenous country, comes in with the lowest trust 1.83/5. Azerbaijan is next, 2.18/5. Other post-Soviet countries are also quite low here. Guess that whole Soviet tolerance thing wasn’t so solid. Swedes come in the highest, as usual.

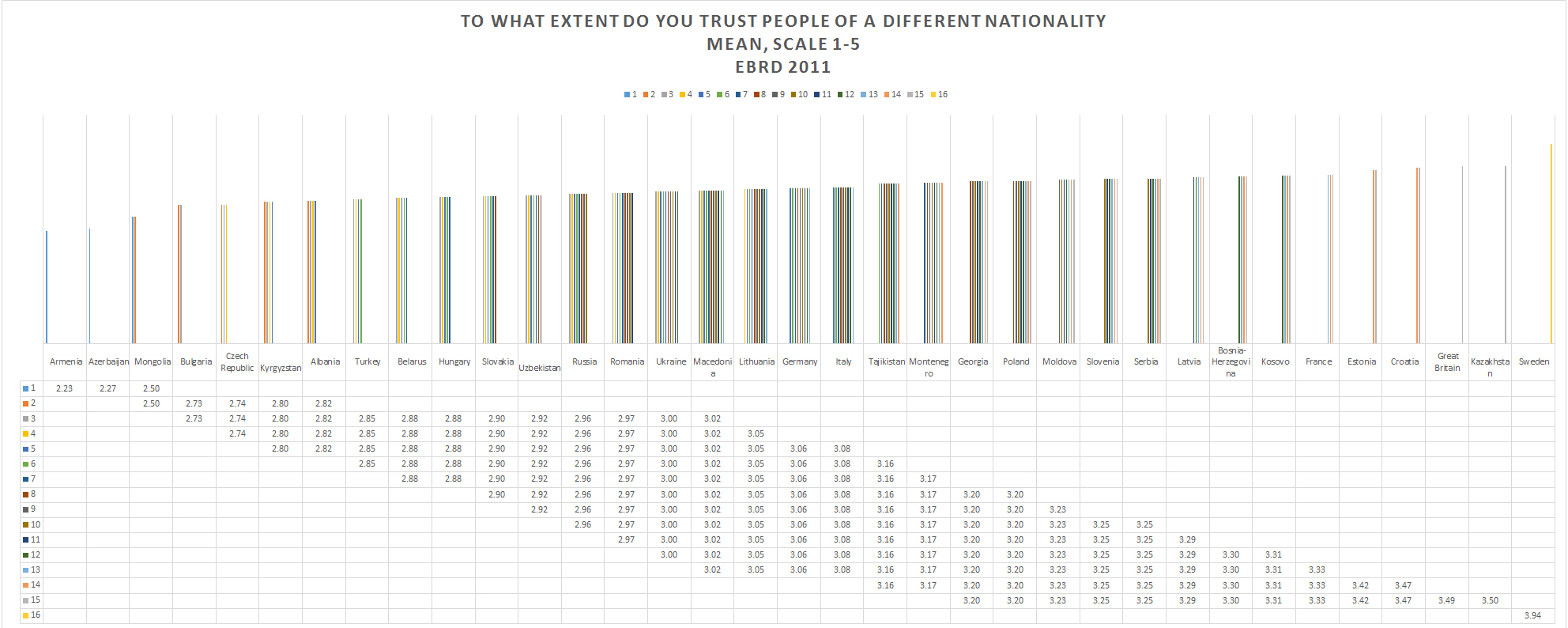

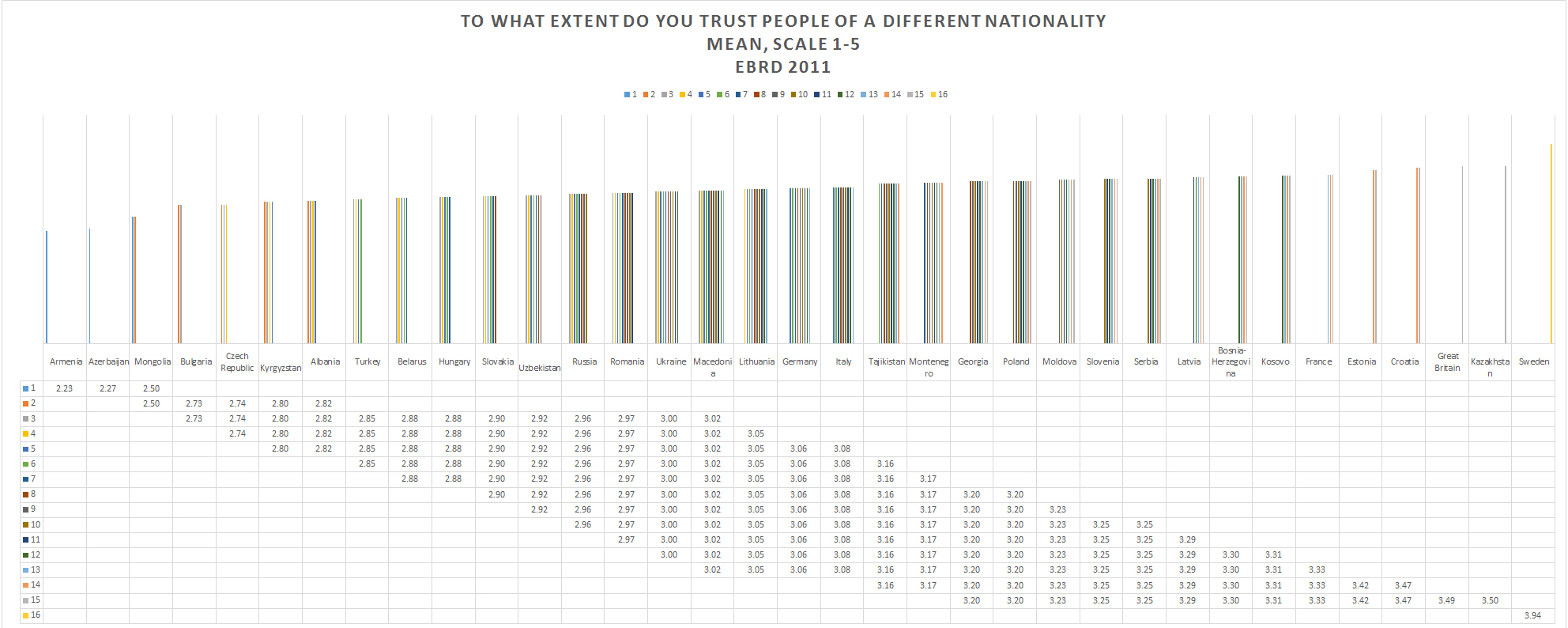

Then trusting people of different nationalities – Armenia and Azerbaijan come in as the least trusting again, with 2.23 and 2.27/5. The most trusting, of course, is Sweden. Kazakhstan is high too, probably because it is so multi-ethnic.

—

So overall, this is important because if people don’t trust each other (in the neighborhood, friends, other people in the country), they aren’t going to be able to engage in positive collective behaviors. They also will be less inclined to want to have good things for everyone – like good healthcare and education.

And, for better or worse, interpersonal trust isn’t easily built.